A review of talks and walks in 2018. These are in reverse order with the December talk first, working back to January

“Backtracking around the Princetown and Tavistock Branches”

Bernard Mill’s opening image of two trains including coal goods at Bickleigh Station in 1962 set the scene for his nostalgic and entertaining talk. Through a series of then and now scenes he took us on a journey firstly up the line to Yelverton.

The original line from Plymouth had already passed over 3 viaducts before reaching Shaugh Bridge platform with its own refreshment kiosk and was frequented regularly by boy scouts and other passengers enjoying the surrounding woods. The 308 yards of Shaugh tunnel led through to Clearbrook Halt, scene of a derailment in 1885, now sadly private and completely unrecognisable.

Yelverton Station with its own turntable and crossing loops opened in 1885 providing for change to Princetown. The station opened up the area to much passenger traffic and Bernard’s superb images showed it in its heyday. The scenes of Plymouth Dairies milk churns carried on the trains, the unusual gravity shunting and the people in their fashions of the 1950’s contrasted vividly with the now inaccessible and totally overgrown state of the present site.

Heading across the moor, Bernard’s pictorial journey took us to Burrator Halt, originally used by the workers building the dam, the old kissing gate still visible today. A snowy scene showed the RAF mast at Sharpitor in the background as the line wound past Routrundle to Ingra Tor Halt. An image of grazing cattle from 1938 marked this spot, also famous for its old “beware of snakes” notice. The first part of Bernard’s tour, after a 3 mile loop around King’s Tor and its quarries, ended at the highest station in England. The branch line closed on a cold and foggy day at the end of December 1956.

Back at Yelverton, we were taken through the old tunnel, over the old road bridge (originally timber built on the design of the Royal Albert at Saltash), into Horrabridge Station. Opened in 1859, it was busy handling copper ore, coal and agricultural products. Stunning old pictures of the Grenofen Viaduct contrast sharply with the modern Gem Bridge as this part of the route now forms the Drake’s Trail cycleway. We end finally at Tavistock South, its original station being rebuilt after 1887 because of a fire. An image of a diesel demolition train on closure in 1964 was offset by Bernard’s final shot of two trains side by side representing the two routes to Tavistock.

Bernard’s superb quality of old and new photos, his incredible recollection of schedules and timetables and his unique delivery made for an excellent evening to round off our year of events.

“The Building of Plymouth Breakwater”

Ron Smith, a new speaker to the society, started his talk by asking the audience some topical questions and after some positive responses, proceeded to tell us about his research.

The breakwater is 60 yards short of a mile long and was built to protect the Sound and the anchorages of Plymouth. 43 feet wide at the top with a base of 65 feet, it lies in 33 feet of water. About 2 million tons of limestone was used in its construction at a cost of £1.5 million.

Beginning in 1788, there was a plan to have 2 breakwaters between Drake’s Island and Barn Pool, and another between Bovisand and the Shovel Shoal (mid-Sound), but it was soon realised that there was no protection from the south-west. In 1801/2 another plan was looked at from Penlee Point into deep water. However, in 1806 John Rennie and Joseph Whidbey surveyed the area in detail and their proposal was accepted in 1811 with the breakwater to lie on the Shovel Shoal, the big advantage being that ships could get out from the shelter at either end according to wind direction.

Whidbey was appointed to superintend the construction and to find the correct stone; a quarry at Oreston, bought from the Duke of Bedford was opened on 1st April 1812. The first blocks were dropped on the Shovel on 12th August 1812 and first sighted above water at the low spring tide on 31st March 1813. The bulk of the breakwater was rubble i.e. rough blocks not fitted together which were tipped over the side of specially built ships. About 50 vessels were used and 306 men employed in the quarry with over 12,000 tons of stone quarried weekly. Richard Trevithick invented a stone-hole borer using a rotary bit for the process.

Storms were a big problem as they displaced the rubble from the seaward side so more stone was needed to flatten the configuration. 100 ton wave-breaker blocks were brought in separately to reduce damage. Concrete moulds were used to make the numbered blocks with c30 still being replaced annually. A lighthouse stands at the Cawsand end and a seamen’s refuge at the other, both made of granite; the fort is not actually on the breakwater and was built, as a folly, in 1860. Construction was finally finished in 1840. Today constant repairs are needed: voids happen which are injected with concrete and the breakwater constantly needs repointing.

Some famous people have visited e.g. Princess Victoria and her mother in 1833. In 1844 tours were started with a bus, under horsepower, being taken out to there to carry people on the structure. There are still trips undertaken by visitors today which can be arranged by Ron Smith.

“A Great and Desperate Venture: Belgian Refugees in Devon during WWI”

Ciaran Stoker kicked off his talk with a dramatic image of a crowded Ostend docks, crammed with just some of the quarter of a million refugees who fled from Belgium to the UK in the autumn of 1914, one of the largest ever movements of people into this country. Ciaran’s research in the Devon Heritage Centre at Exeter had led him through government publications, newspaper and local committee archives and personal correspondence unearthing a wealth of details about the events at that time.

As 8,000 of these refugees came into Devon, a War Refugees Committee was set up in early 1915 under the leadership of Hugh Fortescue to manage the allocation of people and resources across the county villages and finding immediate places to home them. This was later combined with Major Owen’s committee and led to competition over funding. Though there was some help from the Government, fundraising came from numerous sources including concerts, fetes and parades with lots of community involvement and some refugees finding local work. This was all despite difficulties over language, religion and culture and also worries about infiltration by German spies. Another key figure was Clara Andrews who contributed hugely to these efforts and was later awarded a medal by Belgium for her work.

From Alice Clapp’s log book, Ciaran established that the refugees were very diverse, including whole families with servants, total strangers lumped together, children and students, with occupations ranging from fishermen to state officials and businessmen. Some men of fighting age later returned to fight in the war.

The impact on local villages was also quite varied. In Bampton one family consisted of 11 young children and some of the men found work in the nearby quarries. One man however was found to be defrauding the system by not supporting his family and the local committee was disbanded as a result. Many of the refugees did settle well into the local community and some stayed after the war including one family in Ottery St Mary. A family in South Brent returned to visit later and in Teignmouth stands an ornamental urn as a tribute of gratitude from the refugees who took shelter there.

Finally in 1919 the repatriation process began, even assisted by Germany! Huge farewell ceremonies were held in Exeter as the thousands of refugees filtered back home via London. Fortescue’s closing comments were perhaps not endorsed by everyone when he said “our committee is finally closed to the relief of all”. For many, both refugees and locals it had been an interesting experience.

“A Stroll of Discovery around Yennadon”

Following on in her series of walks for our Society around local downs, Liz Miall led us on a quick tour of this popular walking spot full of surprisingly historical interests. First mentioned as Eana’s Hill or Yhanadouna in the 13th century and comprised of metamorphic stone its features include railways, mines, quarries, leats, a reservoir, WW2 relics, medieval and prehistoric archaeology and fine views.

Liz started by showing some photos of troop manoeuvres on the Down in 1873 (12,000 troops passing through) and a reference to a visit here by the author Edith Holden in her “Country Diary”. As we set off, the first stop of interest through the trees was the dome of Dousland reservoir dating from 1906 and fed by pipeline from the Devonport Leat.

At the bottom of the slope we picked up the path of the 1923 horse drawn tramway and noted some of the remaining granite block sleepers along the route. Below the path a shapely stone bridge holds up a drainage culvert. A deep gulley and waste tip further along are the remains of the 1836 Meavy Iron Mine. A blocked adit and shafts and a surviving boundstone can be found further up the hill. Manganese, lignite and ochre were also thought to have been mined in the area.

We passed by the entrance to the quarry which has been working on and off since the mid 1800’s, now producing garden stone. It still employs 18 mainly local people, its immediate future now guaranteed by permission to extend.

At the top of Iron Mine Lane we encountered relics of WW2 in the form of concrete hut bases thought to be associated with a searchlight battery and then passed over a large clapper bridge on the Devonport Leat. Nearby are Bronze Age field systems and a cairn. We traced the circuitous loop of the old tramway and followed the route of the 1883 steam line to Burrator Halt. This was originally just a platform built for the workers on the dam extension in 1924. A 1st class ticket then to Ingra Tor Halt would have cost 9d. (4.5p)

As the light faded we reached the summit of the Down at 301 meters, where once stood a trig point and now a PCWW stone, one of 72 marking the 5, 360 acres of the Burrator reservoir catchment area. We ended our interesting stroll at this superb viewpoint watching the distant flickering of the Plymouth breakwater and Eddystone lights.

“Yelverton Village Walk”

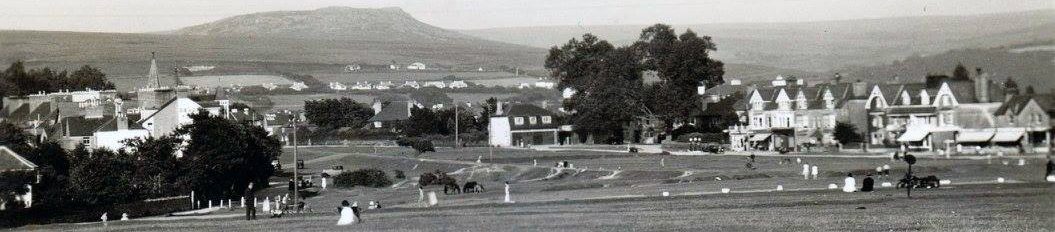

A gentle evening stroll led by Stephen and Claire Fryer highlighted some of the fascinating history of the village. Donne’s map of 1765 shows barely any development in the area and it was not until the mid 1800’s with the coming of the turnpike roads and the railway that major changes started to happen with shops and cottages and a pub appearing at Leg O’ Mutton. The building of the churches and the opening of the railway station, plus Yelverton being portrayed as a healthy place to live led to more houses and the village centre moved across the road to the Green in the early 1900’s.

The opening of Harrowbeer airfield in 1941 hastened further changes particularly to the road layouts and the shops and the airfield’s RAF Harrowbeer Interest Group has done an amazing job in collecting historical details on its website.

We were kindly allowed into St Paul’s church where superb examples of Violet Pinwill’s carvings (one of our previous talk topics) can be seen. Curiously the interior seating is chairs not pews. A plaque sits on the outside wall dedicated to a Typhoon pilot (Paddy Pringle) killed in a crash nearby. The Plymouth and Devonport leats run close by.

The Parade of shops is much changed, the most obvious feature being the lowering of the roof levels because of the airfield. Stephen explained how many of the shop fronts had been extended out over gardens and how the businesses had altered. The Co-Op & Bidders Butchers however have been there since 1906. The 1826 Dartmoor tramway crossed the green and the Texaco garage now stands on the original wharf.

Our tour concluded with an exhibition of old photographs and historical documents in the Rock Inn, courtesy of the owner Sue Callow. Originally a coaching house from the 16th century, a private house until the 1880’s then becoming a hotel. The “Wet Rock” ceased to be a hotel in 1967 and was converted into apartments. Grenville Park, the housing development behind the Inn was originally pasture land for their livestock and the local Surgery stands on what was the vegetable plot. Many of Sue’s photos highlight these changes including images of the old stables, tennis courts and croquet lawn.

Close by, scarcely noticeable is a rescued sign pointing the way to the old Moor House Hotel, originally at Leg O’ Mutton and latterly blown up to make way for Harrowbeer Airfield’s runways

!

“Crownhill Fort – a guided tour”

The first thing that strikes you as you pass through the impressive front gateway is the sheer size of the place, situated high up at the head of 3 valleys but almost invisible from the busy adjacent A386, the inner fort spread over 16 acres.

It was built during the 1860’s and finally completed in 1872 after a series of delaying strikes. Britain had become increasingly concerned at the time about the build up of French military power under the leadership of Emperor Napoleon 111. Lord Palmerston’s government subsequently approved a major upgrade of the country’s fixed defences, including 10 forts and batteries around Plymouth (later called Palmerston’s follies as they were never used in battle).

However, it was used by the military up until 1985 mostly as a training venue in the 19th century, a recruitment and mobilisation depot in WW1, use by Allied troops in the build up to D Day and by 59 Commando Squadron Royal Engineers who provided logistical support to the Falklands Campaign. Its future was secured in 1987 when it was purchased by The Landmark Trust who have undertaken major restoration works to retain its Victorian layout.

Our guide Ed Donohue led us on an extremely interesting tour of the various buildings and armaments including the barracks which once housed 20 men per room, now full of their memorabilia; the officers’ quarters with an earth roof to resist enemy fire (13 roomy casements now self catering apartments); gun sheds and stables and the underground magazine and cartridge stores – an extremely claustrophobic and potentially dangerous area to work.

Walking around the substantial ramparts we were shown some of the 17 guns including the 1811 small bore with its .75 mile range and the even more impressive 1998 replica of a Moncrieff with its 4 ton hydraulic counterweighted barrel and a range of almost 3 miles! – one of only two in the world. Caponniers are situated at each corner of the fort with its smooth bore warship guns focussed on the surrounding ditch leaving no blind spots open to attack.

The evening was rounded off by the firing of an early 19th century field gun. (see picture below)

Today the fort is open to the general public once a month and to pre-booked groups. An impressive and worthwhile place to visit.

“Ivybridge and the 4 Parishes”

Sheila Hancox, a new speaker for our Society, gave an entertaining talk on the birth and rise of Ivybridge, how it grew from being just a crossing point over the River Erme to the fastest growing town in Europe.

Ivebrugge was originally just a narrow 13th century packhorse bridge on the route between Exeter and Plymouth, on the boundary of the four parishes of Cornwood, Harford, Ermington and Ugborough – a total population of c4,000. Although a chapel existed nearby from 1402, it was not until the 16th century onwards that things began to change during the Industrial Revolution with the building of mills to take advantage of the strong river flow, one of which was the Stowford paper mill, built in 1787 and becoming the major employer in the area.

Following the Turnpike Act of 1753 and the arrival of stage coaches on the daily post routes the local roads were widened and a new need arose for overnight stays. The London Hotel (originally the Swan Inn) was built along with a Constitutional Club, a church and houses on Erme Road. Further inns and a new chapel soon followed as the population began to grow. By 1834 a new bridge had been built with another road by-passing the original.

More big changes came with the arrival of the railway in 1848 and Brunel’s iconic wooden viaduct over the river. John Allen bought the paper mill and invested heavily, picking up the business of paper making for all postage stamps; the first post office opened in 1850. 1856 saw the first school and private ones soon followed.

William Cotton, a nephew of the owners of Lukesland, fell in love with the area and bought Highlands House. An avid art collector, he took an active role in the area particularly concerning himself with the eradication of cholera, forming a local board of health. By now the new village had a 5 mile border of its own.

A reservoir to serve the village was built in 1874 plus a police station with its own “Inspector of Nuisances” and the Dame Hannah Rogers School opened in 1887. By 1894 a new viaduct had been built and the village was independent of its neighbours with a population of almost 2,000 and managed by the Urban District Council. The 1911 census shows that people from all over the world were moving to the area.

Wiggins Teape took over the paper mill in 1924 and trade was booming with contracts for all types of security documents including birth certificates and pension books with their trademark watermarks. Changes in technology forced its closure after 226 years in 2013. It is currently being converted to apartments but with a heritage centre.

In 1977 Ivybridge became a Town and during the 1980’s was proclaimed as the fastest growing one in Europe. It is now the largest in the South Hams with over 14,000 residents and still growing. Overlooked by the lofty Western Beacon, it still prospers as the gateway to Dartmoor and the start of the Two Moors Way.

“The Royal Clarence Fire and St Martin’s Island”

Dr Todd Gray returned after his injury last year to explain about the fire which almost destroyed the Royal Clarence hotel in Cathedral Yard, Exeter. It began in the early hours of Friday 28th October 2016 in the Mansion House building and quickly spread to Well House next door; 100 fire-fighters tackled the fire which lasted for hours with the added complication of a ruptured gas main in the hotel.

Todd was called in by Radio Devon to give a background on the hotel to assist with the possible problems resulting from the age of the building as the fire officers did not know the history and the Council had not sent a listed building officer to the scene. He also did many other interviews for TV and Radio.

The hotel consists of 4 buildings: the Central block is the original 18th century part with 2 floors each of stone and timber, but because the building reports had been destroyed, copies had to be obtained to prove the structures did not need to be demolished.

The Royal Clarence is situated in what is known as St Martin’s Island consisting of the properties within the boundaries of High Street, Broadgate, Cathedral Yard and St Martin’s Lane. As some of the shops in the High Street are 15th century these needed to be saved. It took 5 months just to clear the rubble inside the hotel. Mansion House, an 1870s building designed by a dentist was completely gutted and is not going to be restored inside. Inside the Well House (dates from 1500 or before) a well was found in 1936 and thought to have ‘holy properties’ but is now thought to have been a garderobe!

The hotel was built on Roman and Anglo Saxon remains and, as a result of the fire, a medieval banqueting hall has been revealed. The hotel was named after the Duchess of Clarence (Adelaide) who visited in the 1820s; before that it was called Thompson’s (after the proprietor) and called an “hotel” from the 1760s.

Inside the ‘island’ there are 20 houses with no access to the outside with the buildings well documented; amazingly untouched by the blitz. There are a number of buildings on the High Street and there have been lots of alterations over time. Todd went on to list some of them, showing pictures of the changes to the fronts and the heights, giving lists of the occupants and things that have been discovered as a result of the fire. There is still a lot of archaeological work being done with many buildings changed or destroyed.

The hotel is due to be re-opened by Christmas 2019 with an extra floor; it will be modern inside.

Todd has written a book on the above ‘St Martin’s Island – an introductory history of 42 Exeter buildings’ to record his usual extensive research.

“The Roman Excavations at Ipplepen 2007-17 (coins, slate and daub)”

The discovery of some Roman coins by local metal detector enthusiasts in 2007 and a subsequent application by the farmer to put up some new buildings on the site has led to a remarkable 10 year project of tremendous historical importance. Derek Gore related how further geo-physical surveys and trial excavations discovered many unusual archaeological features spread over a large field area near a minor road junction outside the village. The resulting project, led by the University of Exeter and funded by the British Museum has since uncovered evidence of settlements from Iron Age and Roman periods.

Initial finds included a 7 metre deep pit which suggested a Roman quarry containing slate and pottery sherds and a coin dating from the 3rd century. More coins followed and as a larger excavation got underway, trenches and prehistoric field systems were exposed – features such as an Iron Age pit dated c400BC probably used for metal smelting.

One of the most exciting discoveries was that of a Roman road 4 metres wide in places complete with wheel ruts and probably built by their army, which appeared to lead towards Haldon ridge; Derek surmised that this could have led on south westwards towards the River Dart and the coast. Within a side trench the neck of an amphora was unearthed – was this an offering to the Roman god of roads?

In 2014 more excavations uncovered bones from 37 inhumation burials carefully arranged in what appeared to be family groupings and thought to be post Roman c600-800AD. By 2016 burnt bones had been identified of a young female from the mid Iron Age; also a circular building of the Roman period, further trenches, wells, rubbish pits, building post holes plus daub clay and animal dung used in house construction and an intricately designed brooch pin. Later finds included more bracelets, brooches and Samian pottery, all normally the possessions of wealthy people.

An application in 2017 for a new stable by the farmer in the adjacent field prompted further excavations with similar discoveries but also a granary, a blacksmith’s forge containing iron workings and slag, another trackway into the fields and a burial with hobnails from boots thrown in! There was also the incredibly rare find of a pottery sherd from the Romano-British period known as South East Glazed Ware not previously found west of Wiltshire.

It was traditionally thought that Romans never ventured further west than Exeter, however the discoveries near Ipplepen show otherwise. They also show that settlements existed here even well before the Romans, providing new insights into the history of Devon itself. Further Open Days are planned at the site in the future.

“The Last Copper Miners of Dartmoor: a unique legacy.”

With the scheduled speaker unavailable through illness, Dr. Tom Greeves stepped in at short notice with another talk from his vast repertoire of researches. Tom stated firstly that although copper made up 90% of bronze, there were fewer records available and no evidence of prehistoric mining for it on Dartmoor, unlike tin. Copper mining was in fact concentrated in 3 main areas on the edges of the Moor: Tamar/ Tavy/ Walkham valleys, Ashburton and to the north around South Zeal.

Morwellham was a very important port around 1900 for the export of copper from the nearby huge Devon Great Consols Mine and Wheal Friendship at Mary Tavy. Tom had obtained some amazing drawings of the latter which had 6 shafts more than 1,000ft deep in the mid 19th century. The remains of this mine lie hidden in thick vegetation today. Other mines of note were the Druid mine in Yarner Wood, Wheal Forest under Meldon and the Blackdown on the Redaven Brook – the only true moorland one.

Another significant mine was the Ramsley at South Zeal, although it underwent many name changes from its origins around 1780. Tom shared his collection of remarkable images of the mine with its waterwheels , tramways and associated buildings. It seemed that despite the Oxenham Philanthropic Friendly Society being involved, the village and area had a rough reputation, sometimes known as “Irish Town”. The mine closed in 1909 with a huge auction of over 400 items.

Tom’s research does not stop at the mines and their buildings however and extends to the local miners themselves. Again with his extraordinary high quality image collection, Tom has explored their lives by talking to relatives and descendants. These pictures paint fascinating tales of how they far the miners were prepared to travel to find work. John Osborn born 1865, one of 11 children walked many miles to work each day to Golden Dagger mine, often dynamiting a few trout on the way! He also worked in Cornwall, Mary Tavy and India.

A character called Rocky Mountain George travelled to the gold mines in the US. John Newcombe went to British Columbia and Tom read fascinating extracts from postcards sent by Newcombe to his wife in Devon. Another miner joined the Navy and went off to fight in the Boer War. Others worked also in Kelly Mine near Bovey Tracey (iron mine), in coal mining in Wales and South Africa.

The tales and pictures brought to life the characters and the tough working conditions of the mines. For example, images of men with bunches of candles around their necks in preparation for the long descent down ladders in the dark, but also the women on the surface , the “bal maidens” breaking up the ore with hammers.

Tom’s excellent talk and his collection of drawings and photographs also emphasised the resourcefulness of these mining communities.

“The Fair Arm of the Law.”

From his book of the same name, Simon Dell led us through the development of women policing which has its origins in the social changes of the early 20th century, the Suffragette movement and the Great War.

There were no women in Robert Peel’s “New Police” in 1829 though wives of serving officers did have a supporting role as “Matrons”. They were given a small allowance to look after female prisoners, being given a spare key to the double-locked cells for prisoners’ protection. “Wardresses” were later appointed to deal with female prisoners in the courts. Two of these were involved in the arrest of Ethel Le Neve, the lover of the infamous Dr. Crippin, having travelled to the US to bring her back.

In 1895 the Union of Women Workers was formed and during the early 1900’s a series of Special Committees were appointed leading by 1914 to the introduction of the “Women’s Patrols”. The War started and soldiers were billeted in local towns and villages; as a result over 2,000 of these Patrols were established to prevent “acts of immorality”.

At the same time the Suffragette movement was gathering momentum, demanding The Vote and a bigger role for women in society. As policemen and other working men went off to war there was a huge shortage of labour at home which presented a big opportunity for women. This was especially relevant in the munitions industry, large plants being set up and staffed mainly by women (known as canaries because of skin discoloured by the cordite). For mostly safety reasons they employed their own police force. Nina Boyle, a leading suffragette, battled against the authorities to set up the “Women’s Police Volunteer Service”, assisting with the care of refugees, many of whom were often sold into slavery. Although for a long time only supported by private funds they had strict regulations, conducted their own training and had their own uniform, becoming in 1915 the “Women’s Police Service”.

Despite all the good work during the war there was still significant resistance afterwards to the employment of WPC’s, although Commissioner Macready did set up the “Metropolitan Women Police Patrols”. The subsequent influence of Nancy Astor and the outbreak of WW2 then provided a second boost for women in employment.

In the 30 years after WWII, the numbers of women involved in policing gradually increased along with improved training and professionalism. However, it was not until the 1970’s that their role was fully defined. Their duties can now be found in all areas such as underwater and dog patrols, mounted police and traffic. In 1975 the conditions for policewomen were finally made equal to male counterparts.

From Peel’s early beginnings it has taken almost 200 years for the roles of women in policing to be fully established. Many of the police pioneers were heavily involved in the Suffragettes movement and suffered rejection and resentment, but fought hard, proving their worth during and after the two wars to be where they are today.

END