A review of talks and walks in 2017. These are in reverse order with the December talk first, working back to January

William Spreat: a leading photographer of Dartmoor, Devon and Cornwall in the 1860/70‘s

At our last event of the year, our members were treated to the customary complimentary mince pie and glass of wine, followed by Dr. Tom Greeves excellent illustrated talk on the works of this 19th century artist.

Born 1816 in Exeter, he published his first book at the age of 26 in 1842 on the Churches of Devon, images of superb quality including one of St. Andrews in Buckland Monachorum. He quickly mastered all aspects of his art including landscape painting, lithography (only invented a few years before), engraving and publishing. He began to create images as stereographs – 2 prints side by side which when viewed through a stereoscope produced a 3-dimensional picture. Annotating interesting labels such as “looming through the sea mist” he put his stamp on the reverse. He travelled extensively carrying heavy equipment to sometimes very remote locations.

In 1862 he advertised a collection of 300 numbered photos for sale to tourists and visitors at a price of one shilling each. Tom took us through a selection from this amazing work of quite superb quality images from all over the region. Some of the earliest featured coastal scenes of Lynmouth, Torquay and Teignmouth plus another of the Royal Albert Bridge, Saltash with some figures walking along the railway line. He was also keen on the natural world with photos of ferns and waterfalls.

His photos were extremely varied including buildings as well as landscapes and often featured human figures in the background. They also provide great physical and historical comparisons with today and how things have changed. In Cornwall we see his picture of St. Levan church with its sash windows and a thatched building nearby, now no longer there. He labelled Botallack Mine as a “sublimity of nature”. Others included Lanyon Quoit, the Moorswater viaduct and Looe canal and the Holy Well of St. Keyne.

He was very fond of Dartmoor and these images are very interesting for the changes. A photo of Rippon Tor shows a heather clad area – not so today. His image of Fingle Bridge and gorge before Castle Drogo was built is fascinating because of the absence of the dense woodland there now. One of the earliest photos of Wistmans Wood shows it being much smaller back then. Another shows the finely balanced logan stone on Nutcracker Rock and buildings belonging to the New Inn near Hemsworthy Gate, both long gone. In the same picture the prehistoric Foales Arrishes settlements can be seen. However his picture of Manaton Green looks remarkably unchnaged today.

Tom ended his talk with probably the most striking image of them all, taken around 1865 and 40 years earlier than the next known image of mining on Dartmoor. It features a group of miners beside a waterwheel at Vitifer Mine.Thanks to Tom Greeves for the opportunity to see photos that were published around 150 years ago to such an incredible quality and clarity.

George Magrath: Nelson’s Forgotten Surgeon.

There is little general information around on Sir George compared to other surgeons who served with Lord Nelson but Barbie Thompson’s detailed research has helped to highlight the career of a remarkable man. Although some dismissed him as a tall, thin, one-eyed Irishman, Nelson himself described Magrath as “by far the most able medical man I have ever seen” and wrote letters to Lady Hamilton singing his praises.

He was born in County Tyrone in 1775 and learned his trade from 1794 as a surgeon’s mate on board HMS Theseus. He spent time in the West Indies taking part in the evacuation of Guadeloupe but contracted yellow fever and lost the sight in his left eye. However, despite this he soon demonstrated his skills and was promoted to full surgeon in 1797 and joined HMS Russell. He served 4 years here including major naval action at the Battle of Camperdown in the North Sea. Casualties were huge with Magrath performing many operations including multiple amputations but earning great respect and confidence with his skills and alternative remedies.

In 1803 he joined Nelson on board HMS Victory as the flag medical officer. Nelson was very concerned about the health of his crew and Magrath’s skills soon made him a favourite. When a major outbreak of yellow fever broke out in Gibraltar killing over 6,000 people, Magrath was tasked to stay behind to help as superintendent of the naval hospital, Nelson assuring him that he would return afterwards to continue serving with him. Much to Nelson’s annoyance, he was over-ruled from London and William Beatty was appointed instead. Magrath was apparently ‘mortified’ at not being able to share in the glory at the decisive Battle of Trafalgar.

Before the battle he had continued to exchange letters with Nelson but then became a Medical Officer at Millbay Gaol in Plymouth which housed American POW’s from the War of Independence. Unlike his predecessor, Magrath proved to be very popular with the prisoners because of his concern for their welfare and he served there for 9 years. Beatty even wrote to Lady Hamilton commending Magrath for his services.

In 1814 he transferred to Dartmoor Prison where he practised his unique cold water treatments. He treated the injured sympathetically after the 1815 riots and was later praised in many letters and memoirs from staff and prisoners. After the prison closed in 1832 he started a practice in Union Street, Plymouth, using his skills again in the later cholera outbreaks. He continued to live in Plymouth until his death in 1857.

A christening mug presented by Nelson to Magrath was recently discovered in Canada and in 2013 four of the medals awarded to him were sold at auction for over £14,000.

Dartmoor’s War Prison- Constructing, Supplying and Skulduggery.

Due to the scheduled speaker Dr. Todd Gray sustaining a knee injury, Elisabeth Stanbrook kindly stood in, at very short notice, with a new talk, which proved to be very interesting and informative and coincidentally was a good follow up to our recent visit to the prison cemeteries and museum.

Lis told us how Thomas Tyrwhitt, Private Secretary to and friend of the Prince Regent, enclosed 2,300 acres of land to the south-west of Two Bridges and built his estate, Tor Royal. He discovered that the land was unproductive for agriculture and had the idea to build a war prison. At the time there were two other prisons in Peterborough and Bristol but, when these became full, prisoners were held in hulks in the Hamoaze in very bad conditions, packed in like sardines; these were French prisoners from the Napoleonic wars.

Daniel Asher Alexander was to be the architect. A contract was drawn up between the Duchy and Transport board; in 1805/6 they advertised for masons, carpenters, stone cutters etc. The original plan was to construct buildings for 1,000 men, a hospital, Petty officers’ prison and barracks on 15 acres. There were lots of problems during the building: walls collapsing, slow deliveries, bad weather etc. which delayed the finish date of 1807. The barracks were completed in 1809 and 5,000 prisoners arrived on foot from Plymouth in late May 1809. There were further problems such as not enough bedding ordered and insufficient privies; still very overcrowded so new prison blocks were built in 1812 and American prisoners started to arrive a year later.

The water supply came from a leat taken off the River Walkham to a reservoir opposite the prison gate. There were a number of bake houses supplying bread to the prison and some prisoners complained about ‘bad bread’ and after testing it was found to be contaminated with china clay. Milk and dairy produce were also supplied from the surrounding area. Pubs started to arrive, the Plume of Feathers was established in 1808. A chapel was eventually built in 1813 and the French prisoners helped to do this. There were lots of delays with the construction and when the French left the Americans helped to finish it. The church became grade 2 listed, was very damp and rundown and in 1994 was made redundant; it was nearly demolished but was reprieved.

There are a number of the original buildings still in existence: octagonal store rooms, Prison no 1, Prison no 4, with enlarged windows and now used as a cinema, the market place, three of the barracks, the Petty officers’ prison and the hospital.

Today the prison still stands as a stark reminder of the past now housing over 600 convicts. Its history can be read in much greater depth in Elisabeth’s book, on which this talk is based: Dartmoor’s War Prison and Church 1805 – 1817.

A guided tour of Dartmoor Prison Museum and POW cemeteries.

A good turnout of members enjoyed a return visit to the newly refurbished museum and cemeteries, led ably by the deputy governor and museum curator.

We were given a brief history of the prison, now the oldest operating one in the country, category C housing 637 prisoners with only 20 staff! A brainchild of Sir Thomas Tyrwhitt it was built during the Napoleonic Wars replacing the floating hulks in Plymouth. It opened in 1809 with French prisoners and quickly became overcrowded later with the arrival of the Americans, at one point housing over 11,000 inmates. It lay empty from 1817 reopening in 1850 as a temporary convict prison then being re-established in 1917 as a Work Centre for conscientious objectors. Today its future is still unsure.

We were then invited into the museum for a taster of what lies within. This is a fascinating place requiring a much longer visit, housed over several rooms and two floors a huge variety of historical artefacts and photographs. These include items such as model ships, trains, planes and dolls made by prisoners out of everyday materials like meat bones, matchsticks, soap and wood. There is a video containing scenes from the 1932 mutiny at the prison. Old maps, paintings and letters from POWs as they transferred from the hulks sit alongside details of governors’ logs and escape records. Downstairs is the creepy weapons room with displays of prisoners’ creativity, knives made out of sharpened toothbrushes and razor blades, escape tools like guns and miniature mobile phones from matchsticks, plus catapults for moving items around and drone hooks.

Outside, we were then guided under the “Parcere Subjectis” gateway, alongside the forbidding prison walls to the beauty & tranquillity of the two cemeteries. During the Napoleonic and the Anglo-American Wars of the early 1800s, almost 1,500 POWs died at Dartmoor Prison. They were buried in unmarked graves in a nearby field but after complaints in later years of bones regularly coming to the surface, the remains were exhumed and reburied in 1866 in the newly created cemeteries.

They stand in beautiful landscaped grounds, having been significantly revamped in 2002, both poignant reminders of the horrors of war. The French memorial obelisk is modest having been made by prisoners and in 2009 on the bicentenary of the first French prisoners of war transferring from the hulks to the Prison, a ceremony was held here attended by descendants of the prisoners of war and French dignitaries.

The American side is rather grander with an obelisk and its two marble memorial walls containing names of the 271 POWs who died, the youngest of which was only 12 years old. Names such as Placid Lovely, Dumpy Kitre and Shadrack Snell add to the sense of sacrifice.

A guided tour of the Plymouth Synagogue.

We congregated in Catherine Street outside the synagogue (or meeting house) and were given a brief history of the area by Jerry Sibley, the synagogue’s custodian. The street was named after a visit by Catherine of Aragon and buildings have also included a workhouse which then became the police station and a public dispensary. The dispensary and the synagogue were the only buildings to survive the WW2 bombing of Plymouth but the area has been much built up since encircling the synagogue. At one time the street was twice the length it is now with the caretaker’s house facing the street and originally attached to the synagogue, being now above the school room. There was also a Hebrew school, the remains of which are under the Guildhall. A new school was built opposite the entrance in the 1840s.

Jerry explained that he is ˜the slave” who does all the jobs that Jewish people aren’t allowed to do on the Sabbath which starts at sunset on Friday. An ex-soldier, he discovered that the synagogue was likely to close due to lack of funds and had the idea of opening it to the public for free guided tours but receiving donations. He has extensively researched all areas of the Jewish faith and now teaches at schools, 74 last year

We were shown the bath tub deep, tiled and L-shaped and an important part of Jewish life and culture. Men and women bathed separately once a week.

The synagogue itself was built in 1762. The hallway is an extension and holds the rolls of honour from the world wars. Inside, the gallery was extended in 1864 and paid for by Levi Solomon who later went to the USA, changed his name to Simpson and his son married Wallis of Edward V111 fame. In Judaism ladies are the more important and they can sit in the gallery with the children (boys up to 13 only): the men are in charge of the service and have to attend.

The beautifully ornate Ark, built by the Dutch in 1761, is on the eastern wall, made of wooden plaster and having survived the war. It holds the scrolls which are sung during the service. In the centre of the synagogue is the Bimah, the platform from where the services are conducted and built by naval carpenters to look like a ship, again quite ornate with 8 candle sticks topped by acorns.

The congregation kept on growing and at one time had at least 3,500 men with many of its members (as tailors) supporting the local naval economy. As this diminished and houses were not built nearby after the destruction of WW2, many moved away as they were not permitted to drive but only walk a short distance to the synagogue. As a result some moved to London and Manchester and then to the State of Israel which was created in 1948. In 1968 the membership was so low that there was no longer a Rabbi and is now only 39 in the whole South West.

The Synagogue however is a fascinating place to visit with Jerry, a very knowledgeable and entertaining guide.

A walking tour of Moretonhampstead

On a very warm June evening local characters Bill Hardiman and Gary Cox led us on a highly entertaining and informative tour. Granted a market in 1207 by King John, the rent was one sparrowhawk pa. The town has seen much change over the years with a whole series of fires destroying ancient buildings, though many interesting and listed ones remain.

Passing by the restored bus depot, now the motor museum, we noticed the old courthouse, then into Court Street the Lucy Wills Nurses’ Home and Coppelia House, once the home of the wealthy Bowring family. Shops and cottages still show signs of smoke blackened timbers and no. 16 was once the Plymouth Inn, one of the original 16 pubs in the town – only 4 left now. This is a busy street, the turnpike road having been routed through here in 1770, probably to the dismay of Chagford.

In Pound Street near the site of the old slaughterhouse, 3 cottages have been replaced by a restoration project featuring sculptures of animals, birds and legends. The sparrowhawk sculpture dominates the wall in the Square along with a plaque to George Bidder, the famous engineer. The Horse and White Hart still ply their trade as does the Bell Inn around the corner, another ancient inn which once hosted dances and wrestling matches. It also featured as a meeting place for French prisoners housed in Moreton who were on parole.

Many of the current buildings in Fore Street are replacements for those destroyed by fires in the 19C. Fire tenders had to be brought from Exeter and often prioritised those buildings which had fire insurance, plaques on some of the walls identifying them thus. Nearby is the Bowring Library, a gift to the town from shipping merchant Sir Thomas Bowring. In front stands the town’s War memorial. Also here is the old Baptist Chapel, now a Community church, a throwback to the town’s strong non conformist traditions.

The railway came to the town in 1866 and it seems that further tensions with Chagford arose as it terminated in Moreton! It closed in 1964 and is now the site of Thompson’s Transport business. The new car park stands on the site of the old animal market with the old turnpike tollhouse on the corner. Some narrow and quaint alleyways link through to Cross Street.

The eye here is drawn immediately to the almshouses but there is much to see along the way. The old Methodist Chapel is now a workshop and Ponsford House c1740 retains many original features. The 800 yr old cross now has a new tree alongside it, replacing the old oak dancing tree. The Grade 1 listed almshouses date from the 15C, once a workhouse now rented out by the National Trust.

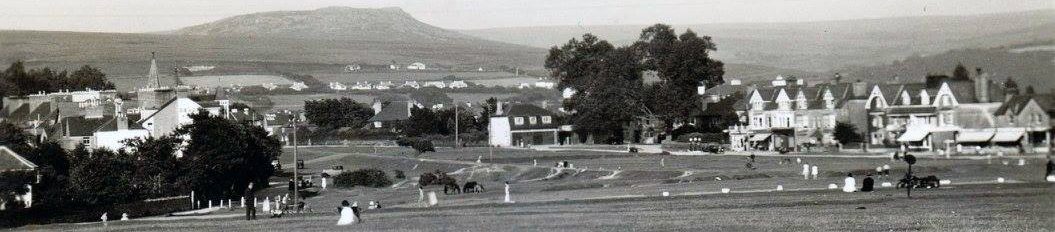

The path through a gate leads to the Sentry, the village green with superb views over Mardon Down. We ended our tour looking in on the 12C Grade 1 listed church of St. Andrew’s, passing then along Green Hill, site of the original market place, and the Arts and Heritage Centre.

Excellent maps and guides are available from the town’s information centre, making this a really interesting place to wander around.

Violet Pinwill: Woodcarver of Ermington and Plymouth

The Revd Edmund Pinwill came to Ermington in Devon in 1880 with his wife Elizabeth and their seven young daughters. The church there was rather dilapidated and he decided to restore it, helped financially by local landowner Lord Mildmay and the architect John Sedding. There was family background in shipbuilding and the girl’s grandfather had been a woodcarver, so their mother decided that some of the girls might like to take up the trade.

Working under the direction of Sedding, 3 of the sisters, Mary, Ethel and Violet soon became highly skilled at the craft and in 1889 set up their own company in Plymouth under the name of Rashleigh, Pinwill & Co., using Mary’s middle name to disguise the fact they were women. Sedding’s son Edmund became an integral part of the team and engaged the sisters to carry out many of his designs for church furniture. The pulpit at Ermington church, installed in 1893 was one of their early pieces, and as with all their work, was carried out using oak.

In 1900 Mary got married and moved away but the other two carried on, picking up commissions from other architects. In 1911 Ethel also moved away carrying on woodcarving in Surrey and Violet now became the sole proprietor under the new company name of V. Pinwill Carvers. She started to win commissions by herself, working from a large workshop employing around 29 other woodcarvers. She travelled all over Devon and Cornwall, mostly by train and bicycle, to meet with vicars and churchwardens to talk about the work they required. She never advertised, owned a typewriter or a car, and did not employ a secretary. It is also believed that during WW1 she worked in an aircraft factory making propellers.

Dr. Helen Wilson’s interest in her subject had started in Morwenstow where she had seen work by the Pinwills on the altar and reredos there. She explained that her research had since taken her to almost 200 churches, reading through their records, and gaining access to Violet’s lavishly illustrated photograph albums of woodcarvings deposited at Plymouth and West Devon Record Office. She has also collected information from family memoirs, newspaper archives and English Heritage listings, postcards sent by one of the joiners, as well as from her church visits.

Examples of Violet’s work exist all over Devon and Cornwall and even as far away as British Guiana. So far, Helen has discovered 645 items varying hugely in design and from Violet’s archive, she led us on a photographic tour of some of the best.

These included a restored medieval chancel screen at St Buryan, 32 saints in the Quire at Truro Cathedral, choir stalls at Lanteglos by Fowey, the beautiful reredos at Ermington, 26 bench ends at Sheepstor, and choir stalls at Yelverton. In Plymouth, a lot of work was destroyed during the blitz, but the photographs record some of these pieces, such as a reredos in Charles Church and a gilded tabernacle top at St Peters.

Violet died in 1957 but examples of her magnificent work live on.

A factious place of backsides & dung-heaps – the lives & times of 17th century Moretonians

By the 1600s the main town settlement of Moretonhampstead had just over 2,000 people and was relatively prosperous, mainly from the wool trade and some tin workings. It had an important role as a ˜gateway on the north-south and west-east travel routes. About 60% of the land was owned by the manorial lords and the Courtenays of Powderham Castle.

The rectors drew income from the glebe lands, tithes and payments for baptisms, marriages and burials. However, before the C17th none of them resided here, one was even given papal dispensation to be the rector at the age of 10 to pay for his education! In his talk Bill Hardiman spoke of the rivalries between Moreton and Chagford and new insights into this “factious place” come from transcriptions of archives by the local History Society.

The first revelation was that the manor was regularly leased out to help the Courtenays ease their financial burdens. Sir William Courtenay (1553-1630) admitted to a lavish lifestyle and ambitious rebuilding projects led to indebtedness. However, Sir Simon Leach of Cadeleigh, a successful lawyer, lent Courtenay £3,000 in return for “all the lordshippe Mannor and borough of Moreton Hampsted”. This indebtedness and the misunderstanding of religious politics at the time probably also explains another intriguing development.

During the C17th Moreton became one of Devon’s foremost centres of Nonconformity, the driving influence being John Southmead, a prominent ˜gentleman”. With his son-in-law, Francis Whiddon, the self styled “pastor”, they set about demolishing what they called â “the Kingdom of Satan”. They strove to curb ˜heathenish sports and pastimes, long haire in men and naked backs and breasts in women”. Difficult tensions in this relatively remote community continued and in 1672 Moreton opened one of the first Nonconformist chapels in the country which competed strongly with the local church.

The power and influence of the manorial system was still quite considerable. Tenants still paid rents to the Courtenays and had to swear fealty to the lord. Copyhold tenants had to supply the lord with a capon each year and pay a heriot or death-duty of their best beast or its value on the death of each life. The widows of the last life had the right to stay on a tenement and could prolong this by avoiding remarriage and ˜living in public fornication with a man”.

Many tenements had “backsides” – burgage plots that were originally for cultivation but were by now often filled in with buildings. There were duties to oversee the woods and rabbit-warrens, the making and retailing of ale and leather, the cleaning of the streets and Kings Highways “dung-heaps” were a particular problem and were closely regulated. Miscreants were fined and there were also frequent pleas of debt and trespass between the tenants providing useful means of income for the Courtenays or the lessees of the manor.

There were significant developments in education although the Rector of Drewsteignton warned of the hazards of teaching “˜in such a factious place as Moreton … of fickle persons … [whose ]minds may alter!”

The Bishop Rock Lighthouse

The Bishop Rock lies just 4 miles west of St Agnes in the Isles of Scilly, facing the full force of storms. Back in the 14th century it was traditional that anyone convicted of felony would be left there to be drowned by the tides, as happened to a mother and two daughters in 1302. Nearby are the dangerous reefs of Gilstone and Western Rocks where in 1707 the Association, flagship of Sir Cloudesley Shovell, was wrecked with the loss of almost 2,000 lives.

Trinity House had been set up by Royal Charter in 1514 by Henry V111 and the first lighthouse was built in Lowestoft in 1609. Various other initiatives followed though they were privately owned until 1836. Requests had been made to Trinity House by the Governor of the IOS in 1818 for a lighthouse in the area because of the dangers to shipping, but it was not until 1847 that work began on Bishop Rock by the chief engineer James Walker. The 120 foot tall iron tower with basic accommodation and a light was completed two years later at a cost of £12,500 but was destroyed by a storm in 1850.

Work started in 1851 on a new stone structure. A base and workshops were established on nearby Roseveare and Rat Islands but the construction presented huge difficulties due partly to the shape of the rock itself. Granite had to be cut and transported from Lamorna Quarry and on one occasion the boat sank in atrocious weather conditions. Stone barges and hulks were also used and despite all the problems, the lamp was lit in 1858 with no loss of life during the building work at a total cost of £34,559.

The first principal keeper was John Watson with 3 others and 4 houses were built for them on St Agnes. Operating on a 3 on, 1 off rota, they boarded the Rock by breeches buoy. They had to buy their own food and baked bread, but were often on rations because of the weather and there were occasional pay disputes.

In 1882, engineer James Douglass and son William oversaw a new design and strengthening of the tower. With an outer casing of granite it was extended to a height of 167 feet with 7 stories including an entrance room, oil stores, bedrooms and living space, at a cost of £64,889. Once again there many difficulties encountered including disputes with contractors and of course the weather but it was completed in 1887.

Elisabeth Stanbrook went on to colourfully describe the lives and tribulations of the keepers. They had to make their own entertainment, were often in trouble, sometimes drunk, for them it was a tough life. One John Ball went outside for a smoke and was never seen again. The work was often dangerous especially the outside cleaning of the light. Huge storms meant they spent time marooned on the Rock and in 1946 a BBCTV crew had to stay there from Christmas until the end of January.

Various modifications and improvements arrived from the 1960’s onwards – fridges, TV, VHS radio and telephones. A helipad was installed in 1975 and the light was automated in 1992. Solar panels came in 2009. The lighthouse is now the second tallest (after the Eddystone) in Britain.

Elisabeth’s talk (based on her book of the same name) was an entertaining and lively account of the incredible feats of bravery and engineering involved and also the amazing lonely lives of lighthouse keepers.

The Road to Messines: Military Mining on the Western Front 1915-17

Rick Stewart’s talk opened with a picture of the strategic Hill 60 near Ypres. In December 1914 the Germans had launched a huge offensive in the race to the Channel and the small force of the British Army was under great pressure to hold the line. Sir John Norton Griffiths, (Empire Jack) saw an opportunity to help. He was an engineer who had developed a new clay kicking technique of tunnelling during his work in the Manchester sewers.

When the Germans started digging tunnels from the high ground to the east of Messines Ridge and gaining ground, Griffiths and a large contingent of men from mineral mines, quarries and collieries were sent to the Front. Throughout 1915 both sides dug masses of tunnels 30 feet down in the soft clay, working in horrendous conditions trying to outflank each other. Mines were exploded by the British and the Germans responded with chlorine gas (canaries were carried in the tunnels as a detection device). Officers were trained to use geophone listening devices in lateral tunnels and there were many close encounters as the two sides broke through and confronted each other. Men with no experience of arms were given specialist weaponry such as daggers and truncheons for the hand to hand fighting underground. Many men died from the fighting and collapsed tunnels.

Griffiths then came up with a plan to dig deeper to undermine the enemy but a German offensive at Verdun forced General Haig to divert resources to the Somme to support the French. Huge mines were blown creating large craters (with names like Lochnagar) but these only gave the Germans places to take cover. A new bigger role evolved for the tunnellers at Arras in 1917. Backed up by miners from Australia, New Zealand and Canada, Griffith’s men had great success digging through the chalk creating huge underground caverns and pushing through the German lines.

Further south however, the French were losing ground badly and control of the Messines Ridge became paramount. Haig resurrected Griffiths’ plan to blow the ridge by tunnelling down deeper to the blue clay, though by now the original tunnels had started to collapse, plus also the Kemmel Sands were very wet and extremely difficult to penetrate. Griffiths however had developed the Tubbing method, an enclosed steel tube which made this possible. This was hugely successful and when 19 mines were exploded simultaneously (supposedly heard in Dublin!) the British took the ridge and 7,000 prisoners in a battle that is hardly ever spoken of or celebrated.

Haig’s next offensive switched to Passchendaele and the tunnellers took on new roles. Here they were employed in building barracks, offices and underground hospitals. When a new offensive was started by the Germans, a further change saw them become combat engineers, blowing up roads and bridges as the forces retreated. After the successful battle at Amiens they then took on the role of mine clearance as the Germans began to retreat and the US entered the war.

Rick’s talk emphasised how critical a part the tunnelling companies played in the defence of the Western Front. Their civilian experiences of digging sewers and working in coal mines and quarries enabled them to drive the tunnels in extremely difficult and dangerous conditions, witnessing the horrors of war and deaths of many of their colleagues. They have never been officially recognised and only one of them, Sapper William Hackett received a posthumous VC. He is remembered on the Ploegsteert Memorial to the Missing near Armentieres.

Dartmoor Prison’s Conscientious Objectors of WWI

Simon Dell’s talk was extracted from his forthcoming book due to be released on the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Princetown Work Centre.

At the start of WWI Lord Kitchener’s recruitment campaign was very successful with people rushing to join up to fight with the expectations of a short war. However, as the war dragged on and casualties grew, particularly after campaigns like the Somme, appetites for fighting diminished and objections increased.

The need for replacements intensified and the Derby Scheme was set up to encourage voluntary recruitment. There was a lot of resistance on political, religious and pacifist grounds. Although there was a theoretical right of objection it was actively discouraged and of 16,000 applications for exemption, only 300 were approved. Despite then the introduction of compulsory conscription in 1916 (the Military Service Act), many men still refused to sign up and were labelled cowards – the derogatory term conchies was born. Public sympathy was not forthcoming and objectors were regularly humiliated by the White Feather League.

After the introduction of the 1916 Act, conscientious objectors (CO’s) were subjected to further biased tribunals assessing their conviction and sincerity. The Alternativists were offered work of national importance such as agriculture and forestry whilst those in the Non-Combatant Corps took on alternative civilian work in the Royal Army Medical Corps or Munitions.

The Absolutists who refused to do any war-related work or obey military orders were sent to prison often for the length of the war. These prisons were run on strict disciplinary and inhumane systems and Richmond Castle was particularly notorious. One group known as the Richmond 16 were forced into uniform and sent to the war front in Belgium. Here they still refused to fight, were punished severely, sentenced to death but then commuted to 10 years hard labour.

In 1917 over-crowded prisons and reports of ill treatment eventually let to the set up by the Brace Scheme of two Work Centres, one of which was at Princetown. Over 1,000 prisoners were transferred here supposedly to engage in work of national importance, though in this case more likely for improving and maintaining the Duchy Estate! The work was very hard, with long shifts digging drainage ditches, quarrying, building walls and roads (eg. Conchies Road the road to nowhere). Poor conditions and meagre diets meant life was no picnic. However the centre was run by CO committees with open rooms; they wore no uniforms and were paid for their work,; they had common rooms and libraries, were allowed outings and visitors, performed plays and concerts and had football teams and rambling clubs. They were common sights around the village but were not popular especially as some of the villagers had relatives still away fighting in the war. There were strong protests in Plymouth and they were often set upon and abused in the village.

When the war ended the men were not released immediately in order to give priority for jobs to those returning from active service. Although released in 1919 many were still subjected to abuse and called cowards. Did they really deserve such a label or to receive such harsh treatment?

END