November

“RAF Harrowbeer – new perspectives”

Stephen Fryer kindly stepped in at the very last minute as our scheduled speaker reported in ill. Our largest audience since we restarted at the hall (perhaps also enticed by our seasonal complimentary mince pies and wine), were enthralled by Stephen’s alternative look at the airfield’s history. His tales of some of the squadrons and their pilots were enhanced by his old maps, photographs and videos.

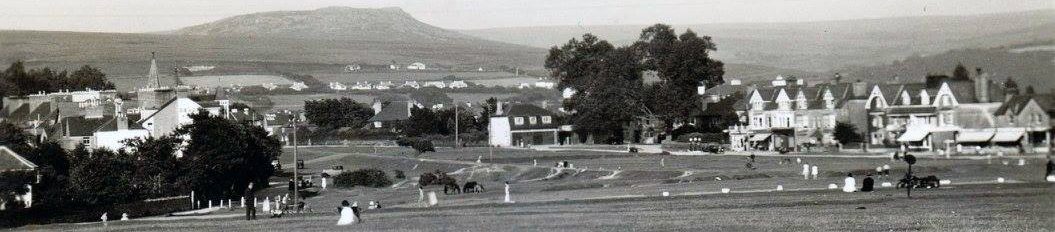

Letters in 1940 from worried locals demanded that the building of the airfield be stopped. However, notable buildings like Udal Tor (a TB sanitorium) and the Moor House Hotel – “the best in Yelverton†soon became builders’ rubble. Roads were rerouted and a new roundabout replaced the cricket pitch. An old map of 1940 was compared to a recent Google Earth one which clearly showed the runway extension. An early picture from 1941 showed a plane having to do probably the first emergency landing at the new airfield.

Stephen went on to talk about some of the squadrons based here including 276 Air-Sea Rescue. Images of a camouflaged hangar and a Walrus seaplane in rough seas were followed by two superb films – the quaint formal commentaries of Pathe and British Movietome News illustrating the techniques employed by the Lysander and Walrus. There was a team photo celebrating 100 rescues.

The Czech squadron no. 312 which arrived in 1942 flew Spitfires and Hurricanes. Their celebrated and most decorated pilot was Tony Liscutin, who Stephen had met. He was involved in the raid on Dieppe and after being chased by an enemy aircraft, faked wounding and hid in the clouds. Despite a hole in his wing, he got back to Redhill (seen in an old photo). Not content to hang around, he took off again in a spare Spitfire for more action and took part in many more air battles. After the war he eventually settled in England.

Frank Mares was another Czech pilot, the first to be awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal in 1942. He later wrote of his war experiences in the book called “Mission Accomplishedâ€. Stephen showed images of the squadron members relaxing around the airfield and another short film of the squadron’s 100th anniversary.

193 squadron was reformed at Harrowbeer late in 1942 equipped with Typhoons. They were funded by “The Bellows of Brazilâ€, a group of expats living in that country who decided to help the war effort by raising monies from public subscription to buy and donate planes.

Some of the pilots from Harrowbeer were members of the Caterpillar and Goldfish Clubs – sharing mutual experiences of survival after parachuting into the sea. One to survive was Killy Kilpatrick whose tail snapped off chasing the enemy near Salcombe and who was left dangling from a tree in his parachute. Not so lucky was Paddy Pringle who died after his plane hit the tower of St. Paul’s Church.

There were some plans in 1960 for Harrowbeer to become Plymouth’s new airport. These were turned down but some of the old buildings were used up until the 1970’s as temporary accommodation for local families. In 1981 a granite memorial was erected at Leg O’Mutton as a tribute to all who served at the airfield. Stephen concluded his excellent talk by reminding us that the old Hoe Café was a recycled blister hangar from Harrowbeer.

October

“Plymouth’s Bloody Historyâ€

Laura Quigley took us through a timeline of events from a volcanic eruption 10 million years ago, through the Ice Age, the subsequent rising of sea levels and the forming of the Plym and Tamar estuaries.

The Bronze Age came and went, followed by the Roman invasions and then the Saxons. Plympton Priory was built by the Saxons, being re-founded as Augustinian in 1121. 1200 years ago, the Vikings arrived seeking gold at Lydford.

When the Normans came in 1066, Baron Baldwin de Redevers built his own castle next to the Priory noticing its wealth. However, when he mistakenly supported the Empress Matilda in her battle against King Stephen, his castle was destroyed by the king.

With Redevers gone, the Valletort family (local gentry based at Trematon Castle) started buying up property in the Sutton Pool area. They had noticed that the main settlement and port around Plympton was silting up, taking income away from the Priory to the area around the small fishing village of Sutton.

The Black Death came to Devon in 1348 and devastated the local population. At that time, the Plymouth area was under attack from the French with the Black Prince establishing his headquarters in the town. The area was a hub of trade with many smugglers and pirates in operation. Queen Elizabeth 1 later recruited them against Spain and backed both Sir John Hawkins and Sir Francis Drake in their ‘travels’ around the world bringing back their bounty. Elizabeth invested in them and had a return of 5 times her investment.

In 1620 the Mayflower sailed from Plymouth to America with pilgrims escaping religious persecution. A Carmelite friary was founded in the town and a map in 1643 shows the seven gates: Old Town, North Gascoyne, Mardon East, Martins, and Frankfort.

In the Civil War that followed, Plymouth supported Parliament and Cromwell and in 1643 there was a battle at Freedom Fields which is still commemorated today. 250 years ago, Captain Cook sailed from Plymouth to Australia to explore the islands of the Pacific. In 1797 during the Napoleonic war there were naval mutinies caused by harsh conditions and poor pay. Napoleon arrived in Plymouth to much pomp and curiosity in 1815 on his way to exile on St Helena. Crownhill fort had been built for defence against Napoleon. In 1943 it became a training ground for 11th field battalion, the names of some trainees called Holmes and Bateman still to be found scratched on walls.

Smuggling was still rife in the area for some time and Laura quoted a poem about a well-known smuggler called black-hearted Joan of Mewstone. Laura also read out a poem about WW1. 2021 was the 80th anniversary of the Plymouth blitz which lasted 6 hours with 8,000 bombs and 700 high explosives. At Boscawen tower in Devonport, under the naval barracks there were 78 bodies, and 18 unaccounted for. A sentry heard voices from under the floor and the 18 were found alive.

From a long time ago, Plymouth has indeed seen its fair share of bloody history. A very entertaining and informative talk relayed with much gusto by Laura.

September

“Okehampton: Historic Gateway to Northern Dartmoorâ€

First mentioned in documents as “Ockington†around 990AD, the town of Okehampton has grown up around the East and West Okement rivers, named after them perhaps. In his talk, Andrew Thompson traced its history and influences up to the present day. Sitting deep in the valley with no moorland views, it might have benefitted from the decline of Lydford as the capital of the moor. The presence of water and rich agricultural land nearby and its location were major advantages, however.

Pre-history records are scarce though there are signs of the iron age nearby. Two sites of Roman forts and a Roman road leading to them (discovered in 2014), along with recent excavations unearthing bread ovens and pottery fragments, have indicated settlements as early as c15-75AD.

During the period from 410-1539, residential settlement was concentrated in three distinct central areas close to the rivers with separate Anglo-Saxon, Norman and Mediaeval influences, but little in the way of change. By the 18th century the town had expanded slowly. It had started to develop a strong agricultural economy with fairs, livestock and Christmas markets and a developing wool trade (North Street cottages were built for weavers). Densely packed streets of timber buildings adjoined the wide main street and some commercial and industrial additions were seen in the form of woollen mills, bottle making and vitriol factories, plus coaching inns with stables.

Prosperity as a market town increased due to the wealth and influence of new landowners and the presence of the castle. Situated on a very strategic spur of land dominating the centre of the town, it had started as a motte and bailey with a keep c1068, under the ownership of a feudal baronry. Rebuilt in 1300 its role changed with the Courtenays, becoming a luxury hall and social centre with its new deer park and associated hunting events. The family’s dramatic demise did limit development thereafter for a while.

Other influential landowners included the Saviles who built the classical mansion house “Oaklands†and Sid Simmons the draper and sales rep who had made his money from carpet cleaning patents. He designed, built and paid for the superb attractive park with its romantic Swiss chalet. Tourism started to arrive in the early 1900’s attracting painters and artists like Turner, inspired by the area’s scenery and heritage.

The turnpiking of the roads and the coming of the railway led to further expansion and development. Town centre road improvements followed and a new suburb was created with residential housing now reaching out beyond the central area where it had been concentrated for centuries. A permanent army camp was set up in 1894.

In the 20th century however, the bypassing of the town by the new A30 trunk-road may have reduced its function as the Gateway to the Moor. Huge development in the last 20-30 years have turned it into a commuter town for Exeter.

Andrew’s illustrations, particularly his maps, provided graphic images of how the town has changed over the centuries….a quiet riverside settlement centred around the rivers for hundreds of years into much larger and sprawling residential area. Still lots of historical interest though – worth checking out The Museum of Dartmoor Life in the centre.

August

An evening walk around Lydford

A group of us met in the Castle Inn car park for a guided walk around Lydford on a grey but dry evening with renowned historian, Andrew Thompson. Andrew gave us a brief history before starting the walk:

Lydford is a Saxon settlement, one of the most important sites in the country. It is 1 of the 4 Devon towns in the Burghal Hidage, a 9th century list of fortified towns or ‘Burhs’ in the Saxon Kingdom of Wessex; the others being Exeter, Totnes and Pilton (near Barnstaple).

Lydford has a street pattern consisting of a main street with lanes leading off at right angles with earth defence walls which once surrounded the town. Excavations have been done and show that the defences were built in 2 phases. The first bank was built with turf supported by a timber structure and later the front of the rampart was faced with granite blocks. The town has a well-defenced position on a promontory with the gorge below.

The 4 towns were mainly administrative centres with a mint of which the evidence is in the coins. From 973 to 1050 Lydford made about 1 million coins; about 400 survive from the reign of Ethelred, most are now in Scandinavia as they were used to ‘pay-off’ the Vikings. The Domesday Book says that there were 28 dwellings in the town and 40 laid waste, the latter probably outside the town. There were probably 3 generations in a home i.e. about 6 persons per house.

Andrew then took us to the remains of the small Norman castle or ‘Ringwork’ – a roughly triangular enclosure protected by a high rampart with a deep ditch; a relatively rare and early form of Norman building. Excavation has revealed 5 structures inside the castle and evidence of peas, beans and charred oats so it may have been a distribution point. The castle probably lasted a 100 years before being abandoned. The church of St Petroc nearby has some 13th century building but it is mostly 15th century. It has a Saxon or early Norman font and there are some fine slate tombstones.

The ‘newer’ Lydford castle is medieval, constructed in 1195 and is a stone tower of a motte and bailey design. Andrew Saunders excavated the bailey with trenches and found Saxon pottery and evidence of earthworks down to the gorge. The castle was always intended as a royal prison and it seems at some stage to have been involved with tin stannaries and with agriculture. In the basement well-charred grains and a water spout have been discovered plus a window that shows that the mound was created after the castle and, therefore, not a genuine motte and bailey castle. In the 1230s Lydford was transferred from direct control to Richard, Earl of Cornwall. He filled in the basement and built on top, creating a grand hall for entertainment, a court room and a solar plus administrative rooms. There was more building done in the 18th century.

Andrew gave a very interesting talk as we went around these historical features and we thank him for leading us.

July

“A Gentle wander on Dartmoor”

26 members and friends gathered at Pork Hill carpark on a warm July evening for a circular walk with retired Dartmoor ranger, Paul Glanville.

Paul’s style is to stop at various points along the way and ask the group to speculate on what they are seeing. It wasn’t long before their thoughts were tested by some innocuous looking earthen and stony banks. No real conclusions were forthcoming – maybe hut circles, more likely ring cairns thought Paul.

Next were two upright stones forming what looked like a stock gateway, though higher than the adjoining banks. Remains of medieval enclosures are criss-crossed here by prehistoric boundaries called reaves – a good example of how different periods of history overlap.

A geology lesson followed, something that Paul is good at, though personally I struggle to take it all in. He explained how the tors were formed after a massive upthrust in the earth some 270m years ago and how sea levels here were much higher. Also, how differences in the heat of the underlying rocks have determined the sources of tin and copper.

We paused at some cuckoo spit on the gorse – the frothy liquid secreted by froghoppers, sometimes known as “spittlebugsâ€. Further on, a flat stone provided a fine example of the pre 1800 method of rock splitting called wedge and groove.

Time for some group photos and some leat hopping at Beckamoor Cross, better known as Windypost. The intricate, partly chamfered and leaning cross stands as a marker on the 16th century Jobbers Path, some say also the Abbots Way. Adjacent is the 18th century Grimstone and Sortridge leat, built to serve the two ancient manors in Horrabridge. Bullseye or incher holes regular the sharing of the waters now with nearby farms and private dwellings.

Also close by is a flat stone with several small holes and the scant remains of a building – revealed to be a blacksmith’s testing stone and adjacent workshop. On the banks of the leat, a good example of the post 1800 stone cutting technique called feather and tare can be seen.

Following along the leat, we came across the wonderful wheelwright’s stone and the ruinous remains of a large blacksmith’s shop. Deep in the bracken below the leat, Paul’s final discovery was the outline of a 14th century medieval longhouse.

Paul’s whistle-stop tour highlighted how much can be seen but easily missed on a short walk, but also how rich Dartmoor is in history through the ages. Prehistory, medieval, modern, geology and wildlife – all carefully explained with typical added humour by our guide.

June

“An historical walk on Plymouth Hoe“

Standing next to the historic Mayflower Steps on a warm June evening, surrounded by tourists enjoying the sunshine, it was hard to visualise what the area looked like in 1620. Our expert guide Chris Robinson did his best over the next 2 hours to take us through 400 years of history and an appreciation of the “Ocean Cityâ€.

At the time of the Mayflower sailing, we would have been looking across to the fish market and the “cawseyâ€. Now we’re on the West Pier, the causeway and a further east pier gone, and the market relocated (twice). Sutton harbour had taken over from Plympton as the main port for trading of tin and Plymouth with c8,000 residents was one of the largest towns in England.

Behind the Admiral McBride (1790) stood the old castle, the Fisherman’s Arms (1750) still utilising one of its old walls. We paused at the delightful “Fisherman’s Restâ€, a quiet corner and gift from Lady Astor.

The road to the Hoe was established in 1934 when Cromwell’s victualling yard was demolished, extending now into the beautiful promenade of today. Two striking figures painted (despite the bureaucracy) into the steep grassy banks below the Royal Citadel greeted us around the corner. Similar figures were carved here before and legend suggests that Brutus the Trojan commander’s mighty warrior Corineus had hurled Gogmagog off the cliff here and rewarded him with the gift of Cornwall.

Taking in views of the 1mile long breakwater and the old Staddiscombe firing range walls, Chris pointed out the Napoleon Bonaparte feature, erected in 2015, the 200th anniversary of Waterloo. Here he had been briefly kept prisoner on a warship in the Sound en-route to exile on St. Helena. Boats filled the Sound and thousands lined the Hoe to see him, music playing in a party atmosphere, to which he reportedly responded by posing and waving his famous hat!

More views unfolded as we crested the hill – across to RAF Mountbatten, a Sunderland flying base in WW2. Chris related how T.E. Lawrence (a friend of Lady Astor) had spent time there. The pier of 1880 has gone but Smeaton’s Tower was dismantled around the same time from the Eddystone and still stands proudly on its current site.

On the top promenade, stands the 10ft high Drake’s Statue (1884), a replica of the one in Tavistock as they got their funds first, from the Duke of Bedford! The National Armada Memorial followed soon after in 1888 on the 400th anniversary of its first sighting – Chris pondered on whether Drake finished his game of bowls first. The Royal Marine memorial (1921) and the Viking stone (1997) concluded our tour.

This summary hardly does credit to Chris’s knowledge and highly entertaining descriptions of Plymouth and its history. Recommended read is his book on the topic “Plymouth 1620-2020â€. We are hoping to follow up this walk next year with a Part 2 – The Barbican.

May

“The History & Art of the Catacombs of Romeâ€

Roman law at the time prohibited the burial of the deceased within the city walls and Christians did not agree with the pagan custom of cremation. Because of a lack of space and the high price of land they decided to create these vast underground cemeteries, in an area of soft volcanic soil which hardened in the air.

Dr. Geri Parlby described how over 60 catacomb sites deep underground covering hundreds of miles, containing thousands of bones, and dating from the 1st – 5th centuries have since been discovered. The catacombs consist of large numbers of subterranean passageways and labyrinths with rows and rows of rectangular cavities dug out resembling bunk beds. The corpses were wrapped in shrouds and placed in the niches, then sealed with baked clay, covered in slabs, often with the name of the deceased carved on the cover, accompanied by a pagan symbol.

Wealthier citizens could afford their own special rooms with decorated archways, wall and ceiling frescoes and symbols like the Medusa and the Labours of Hercules. Christians hid their faith behind these pagan images in a sort of code, taking many stories and themes from the Old Testament. Geri described how these included Orpheus the Good Shepherd, Ichthys (the Jesus fish), Jonah and the Whale, Adam and Eve, Noah, Moses, and many others.

By the end of the 3rd century more sacred texts were included featuring redemption and resurrection, though no images of Christ’s birth and death. The 3 Wise men and the Adoration of the Magi did appear, but in strange non-Roman (barbarian) outfits. The baptism of Christ and images of Lazarus and banquets were also popular.

In the early 4th century, Constantine the Great became the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity, proclaiming religious tolerance with his Edict of Milan. Saints and Martyrs now rushed to be buried in the catacombs, often willing to make big payments for the privilege. Tradesmen too like coopers, weavers, shepherds, and stonemasons had their own crypts with their individual decorations.

Soon after however, many of these bodies were moved to the new churches being built, people now freely able to visit and pay tribute and make pilgrimages to the tombs. Early restorations were unfortunately vandalised by invaders like the Goths. During the 8th and 9th centuries all the relics from the catacombs were removed for security purpose by order of the Pope and as idolatry was subsequently condemned, the tombs deteriorated.

In 1578, the catacombs were re-discovered by builders. They have been re-interpreted by Vatican scholars, (often in cartoons) and over the centuries since, science has prevailed.

Geri’s talk illustrated the rich variety of the art within the catacombs and the innovative and secretive attempts of the early Christians to disguise their beliefs. Today, we are fortunate that 5 of these sites, among the oldest in the world, are now open to the public outside of Rome.

April

“Dartmoor’s Moss Gatherers in WW1â€

During World War 1 the fields of Northern France and Flanders were destroyed by the conflict. One of the first plants to germinate was the poppy, but another found elsewhere which had a more practical role was sphagnum or bog moss as it was used in the preparation of wound dressings for which there was great demand.

Dr. Ann Pulsford’s talk explained the uses and qualities of this plant and the role that Dartmoor played in helping the war effort. 17 million were wounded in WW1 and the aim was to get as many as possible back on the battlefield, fit for duty again.

Dressings and bandages were made from a variety of materials including net curtains and cotton though this was scarce as it was used to make cellulose in gun cotton for explosives. Moss was a cheap alternative and Sphagnum papillosum was the best species as it is more absorbent than cotton. The moss has antiseptic qualities like iodine, which was in short supply, and also prevents the growth of bacteria in the wound, healing faster. Men with sphagnum moss dressings could be transported from battlefield to hospital without disturbing the wound.

Harvesting and processing of moss took place on an industrial scale and by 1918 Britain was producing 1 million dressings per month. Dartmoor’s bogs were recognised as good places to collect moss as they had the waterlogged conditions that the moss needs to grow, becoming a major collecting habitat. Most gathering was done by women and children, the women also making the dressings. Collectors were out in all weathers including the Boys Brigade, Boy Scouts, Girl Guides and local volunteers.

The moss was picked over to remove twigs and dead frogs and then dried outside on wire trestles or inside on drying racks. The dried moss was sewn into 10×14†dressings, packed and sent to medical dressing stations and hospitals. Moss gathering depots were set up at Widecombe and Princetown, where Edward VIII funded a centre and made an official visit to see the operation. Mary Tavy and Okehampton also had centres as did Dartmouth, Tavistock and Plymouth. Scotland and Orkney also had collecting centres.

Mosses are primitive plants and have existed for at least 470 million years, having many other uses. Sphagnum moss is the only one of economic value. In Mexico moss is used as a Christmas decoration. Wads of moss were once used to line pits for the storage of vegetables and to seal cracks in cottage chimneys. A 5,000 year-old body found in a glacier in the Tyrol had moss stuffed into its clothing as insulation. Laplanders and Canadian Indians used moss and reindeer hairs for children’s cradles, Eskimos using it for nappies and toilet paper. Decaying moss is a major component of peat which is used in smoking malt Scotch whisky.

Ann’s talk and images of the volunteer collectors and stations fully highlighted the importance of their efforts and the role of Dartmoor’s bogs and its mosses.

March

“The Black Death on Dartmoor”

The story of the 14th century disease is one of resilience, great social change and adaptation, well presented in Dr. David Stone’s “virtual†talk.

Life on Dartmoor before the plague centred around isolated and few farmsteads, though the population overall was slowly growing by the mid 1300’s. Tenants were mostly beholden to the lords of the manors who enjoyed high status with their mill buildings and large landholdings. The surnames of the local population often reflected their occupations e.g., Potter, Taylor, Taverner and they worked for their lords.

Oats, wheat and barley were grown and sold through the mills and the local markets at Chagford and Newton Abbot, along with rye and straw. Cider and cheese, soap made from bracken and flax were also products of the moorland economy. Cattle, sheep and goats were reared on the moor and the tin industry gathered pace. Generally, however, wages and conditions were poor, taxes had to be paid to the masters and health and hygiene also suffered.

In 1348 the bacillus, thought to have originated from marmots, arrived from Western China, probably via the traders on the Silk Route. Despite villages being isolated and barns being closed, the effect was devastating. Sickness was followed by armpit boils, fever, headaches and vomiting. Although it took around 6 weeks to develop, there were no remedies and victims generally died within days. The church decided it was brought on by the wrath of God in punishment for the populace “wallowing in wickedness, evil and depravityâ€. Priests themselves suffered, 75% of them having to be replaced – 40-50% of the population of England died from the disease.

By 1351, two thirds of the tenants had new owners in the now deserted landscape. Churchyards were full, there was a huge stench over the land, families had been torn apart, crops ruined, farm animals dead and tin output down. Tenements were abandoned and land forfeited through lack of tenants and unpaid rents.

However, within 30 years most of the farms were working again and levels of consumption were growing. The social balance had changed with more and more tenants now free of the restrictive practices of previous landlords. Wages rose, there were more jobs especially for women. There was a huge effect on the economy of the region, tin output grew, fulling mills expanded, sheep and cattle numbers were up. The populace enjoyed better quality bread, ale and clothes. There were improvements in health and hygiene.

This progress continued over the next 150 years as the population on Dartmoor grew still further. Astonishing that it took something of this nature to turn around years of entranced social conditions leading to improvement and thus a lasting tribute to those who survived.

February

“Dartmoor’s Georgian Improversâ€

In February Simon Dell kicked off our new series of virtual talks with 33 members tuning in.

The Hannoverian period 1714 George 1 up to Queen Victoria in 1837 saw many changes to the activities and lives for the people of the Moor. Early agricultural practices consisted of ridge and furrow enclosures (Challacombe lynchets) and hand ploughing and seeding, though Jethro Tull’s seed drill in 1701 had started to see some mechanisation. With the end of the plague in 1720, the pace of change picked up.

There were still epidemics however such as smallpox and living conditions were poor. Despite this, the population gradually increased with people keen to expand their horizons. Clapper bridges were built over rivers for packhorse tracks, new routes appeared such as the Abbots or Jobbers Way, the Lych Way and the Tavistock to Ashburton Track. By the mid-18th century, new turnpike roads were being built making travel across the Moor quicker and easier.

There were many farms on the Moor but life was still difficult and basic however, given the unsuitable conditions and climate. Lime was burnt for use in improving the soil and in construction of buildings. Potatoes were grown and sent to markets such as at Two Bridges and there was a growing wool industry.

Visions of a much more thriving and prosperous Dartmoor came with the arrival of Thomas Tyrwhitt to the area. A man of some renown serving as Secretary to the Prince of Wales amongst other roles such as local MP for Plymouth and Okehampton, Lord Warden of the Stannaries and Black Rod, plus being an MP for the “rotten borough†of Portarlington in Ireland! He was knighted in 1812. He founded Princetown and his ambitions were boundless, if somewhat flawed.

From his new home at Tor Royal, he put the village on the map with his building projects. He hoped for great prosperity from such as growing flax crops for linen, turnips and potatoes and the water supply to Devonport. When most of these failed, he was presented with an opportunity from the wars with France and the US, leading to the building of the prison for the POW’s. Even this had a short life closing in 1815 after a mutiny and the end of the conflicts. It was not until 1850 that it re-opened as a penal colony.

However, the Moor did see many other improvers making their mark during the 1800’s with the granite quarries of Foggintor and Haytor, china clay, peat working and the associated tramways (P&DR 1823), the Stover Canal and Templer Way, and the GWR railway of 1876. One way or another, the Georgians had a major impact on life on Dartmoor.