RUMLEIGH HOUSE VISIT

On another beautiful sunny evening, courtesy of the current owners we were shown around the old estate of “Rumley “on the banks of the River Tamar. The Grade 11 listed house had been empty for 5 years and is now undergoing major restoration works. Jonathan explained in detail the history of the 300-acre landscape which is thought to have 14th century origins. Most of the development however has been from the mid 1700’s with major changes and improvements taking place with different owners.

One of the earliest of these was a merchant and Mayor of Plymouth called Thomas Darracott who probably used it as his family’s country retreat and a symbol of prosperity .With income available from the farm he was able to add extensions to what was then a much smaller house. Later, wealthy and influential developers included the Youngs, Franklins and Crofts who tailored the estate for different purposes including market gardening, building huge oil heated greenhouses and stabling for horses. In the early 1800’s the landscape was further developed with new driveways, gardens, woodland and riverside walks. Extra brickwork wings with hanging slates were added to the house to accommodate servants’ quarters and a library. In 1820 it was described as a “genteel mansion” by the poet Carrington.

Huge Monterey pines and other ancient trees now dominate the wooded gardens though remains can still be seen of an old, curved wall and “ha-ha”. We walked down through fields to the old quay on the river, passing an 18th century hollow way, quarry and WW2 bomb craters (it is thought that munitions may have been hidden under the trees). Further along on the edge of the riverbank are the remains of a fascinating stone summerhouse with cobbled floor, probably once used for boat stops and a pleasant spot to entertain and relax. A nearby 1769 lime kiln is indicative of previous industry.

Christopher’s tour of the house interior is hard to describe with around 20 rooms undergoing significant restoration, although adorned by their own period artefacts. The rooms include a reception hall, drawing room, dining room, library, study and telephone room, kitchen, scullery, laundry, stores (once a dairy and apple store) plus old fireplaces, bedrooms and bathrooms. One room once even contained a floor to ceiling bird cage. The south wing has a self-contained holiday cottage.

We concluded our visit in the recently restored walled garden with its beautiful shrubs , flower borders, fruit orchard and ornamental pond, with tea and biscuits served up by our excellent hosts.

Jonathan and Christopher have taken on a massive project, achieving a lot already but with much still to do. So much history is contained within the listed house and grounds and as part of the Tamar Valley National Landscape it is surely worth preserving. Every effort should be made therefore by the various bodies to assist in making this possible.

BERE ALSTON – A GUIDED WALK WITH Clive Charlton

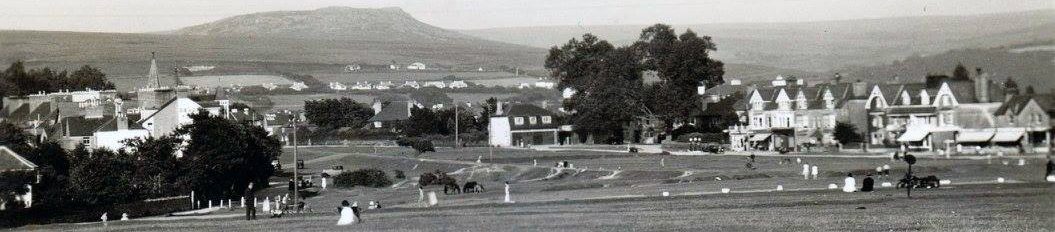

Above: Station Road and Ebenezer Chapel 1920 – courtesy of Clive Charlton

On a nice sunny evening, Clive led us around this old historic mining settlement supplementing his talk with many interesting old photographs.

Starting on the old site of Curly Jack’s shop, Clive explained how the original hamlet was founded on a hilltop at the head of a valley. Its name stems from being on a peninsular (Bere) and probably a Saxon chief Althamston, later becoming part of the lands of the de Ferrers family.

It grew in importance in the late 13th century with the discovery of silver and lead which was much in demand for use in the continual wars with our European neighbours. This led to a huge influx of miners and their families from around the world. With the additional growth in the horticultural industry, it was also granted market and borough status.

Clive mentioned the variety of water sources as we passed up Tap Hill pausing to look at an old well. Other notable buildings were the old blacksmiths (Anvil House) and the old post office built of Roborough stone. In Bedford (prev. Gallows) Street stands the oldest house. . He said that despite Chapel Street having an old nickname of St. Giles in the Fields it was probably a slum!

We moved on through Drake’s Park, its curved road design indicative of earlier medieval strip fields. Crossing over Broad Park road (the original direct route through to the river), we paused at the amazing views of Calstock and beyond.

Broad Street, a 20th century development, led us into Station Road, formerly Frog Street and changed with the coming of the railway in 1890. Here is one of the oldest primary schools in Devon. Founded by Sir John Maynard in 1665, the original red doorway still stands with the date carved into the porch.

With the revival of mining again in the 15th century, albeit with new technology, the population increased significantly. There was lots of billeting in Lockeridge Road and the building of several chapels. The Parish hall opened in 1912, financed by the Edgcumbes and their rental incomes. It enjoyed life as an early cinema and was used a lot for supporting WW2 activities.

The village was also notorious for being a “rotten borough.” It was declared in 1580 as a parliamentary constituency and many prominent landowners and gentry folk took advantage to secure their seats in power by dubious means. Cornwall (prev. Pepper) Street housed the burgage holders, the only ones entitled to vote, leading to much local friction and bribery. This all changed with the 1832 Reform Act.

We ended our walk in The Square, a site built for miners and their families and sponsored by metal engineer Percival Johnson. In the 1851 census there were 84 residents living here.

This was a fascinating stroll around this ancient village enhanced greatly by Clive’s extensive knowledge. The area is much changed now from its early origins with a lot of new development and facilities, but its history remains as interesting as ever.

“Fishery Friction: tales of fish related disputes on the Tavy”

A talk by Dr Sharon Gedye

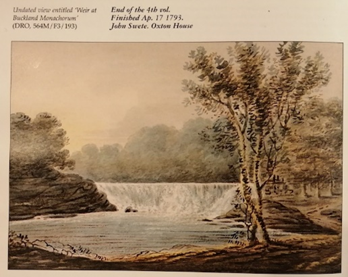

An image of the Buckland Abbot’s Weir copied by permission from Dr Sharon Gedye’s blog entitled “A walk in English Weather”

Sharon started the talk by introducing herself and explained her interest in the Tavy Fisheries as that of their historical importance but lack of appreciation by the region’s heritage.

She first explained the difference between mill and fish weirs and how a fishery operates, in particular the use of weirs to control the movement of fish upstream. Two of these existed on the Tavy called Drake’s and the Abbot’s weirs. Fishery owners extracted the large, trapped fish with boats and nets downstream of the weirs.

Sharon focused on a few key episodes that demonstrated the conflicts and challenges faced by the Tavy fishery:

The fight at the new Buckland Abbot’s fish weir in 1280 between Thomas Gyrebrand, the forester to the Abbot of Tavistock, and a number of Buckland men who were chopping trees down in Blackmoorham wood which was near the weir. Thomas was shot by an arrow made of ash and headed with iron and steel and none of the Buckland men saw who shot him. Thomas was gaoled for bringing a false claim of robbery and ordered to pay ½ a mark. Two of the Buckland men were ordered to pay 1 mark each. The jury decided that the men were in the right to take wood from the Tavistock side of the river.

Thomas Drake v William Crymes 1601: this was caused by the post dissolution havoc whereby estates were broken up with different owners. The lease of the fishery to Drake in 1592 included permission to build a weir and a corn mill. William Crymes owned the manor of Buckland and threatened to dismantle the weir so that he could build his own as he was claiming the fishery belonged to him. Drake petitioned Lord Mountjoy to intervene. This dispute involved many legal and physical confrontations over fishing rights and weir ownership over a long period of time.

A dispute between Buckland Abbey and Maristow 1690s to 1750s: Sir Andrew Slanning claimed rights to the fishery leading to long conflicts and poaching incidents. In 1706, Nicholas Bailey and some other men said they had witnessed an incident of poaching some years previously by servants from the Maristow estate who were fishing in Old Wood and had arrived in a boat. They were asked to come ashore and some did but they all ran away except one, Will the Potter. Nicholas Bailey said he took the net and rope away but Will kept them away from the boat with a long pole.

The demise of the weirs: the destruction of the weirs in the 1860s increased pollution in the river from mining activities. This caused the fish to sicken and die and finally led to the formation of the River Tavy Fishing Association.

In conclusion, Sharon emphasised the historical significance of the Tavy fishery and associated weirs but noted that it remains a poorly understood but crucial aspect of the region’s heritage.

The Industrial Archaeology of the Upper Plym – a talk by Ernie Hoblyn

Dewerstone Winding house and wheel 1912 (courtesy of Ernie Hoblyn)

A talk by Ernie Hoblyn

Ernie related how walking his dog and wanting to find out more about what he was seeing, inspired him to research and write a book about the Plym Valley. For our talk, he concentrated on the upper valley from Shaugh Prior.

He first described the old railways of the Plymouth & Dartmoor Tramway (1823-1916) and the subsequent Tavistock & South Devon (1859-1962). Granite was brought off the moor to Plymouth via Cann Quarry and Crabtree; in the early years horse drawn on the P&DRT, later replaced by steam. The old incline plane to Lee Moor can still be seen, along with remains of workers’ huts and stables at Plymbridge. China Clay was also transported by rail until 1939, when it was replaced by piped slurry.

On Roborough Down from the Yelverton Golf course down to the River Meavy at Clearbrook, can still be seen remains of Yeolands Tin Mine, a deep mining venture from 1848. The old mine captains house is occupied and seen nearby are ruins of buildings, an adit which still supplies clean water to nearby houses and various old shafts, some of which have recently opened up through collapses. Copper had also been discovered during the building of the Leighbeer railway tunnel. Another local mine was the Bickleigh Phoenix and like many of its kind produced many false promises of wealth!

The Shaugh Bridge area is particularly interesting with remains of various industries. Three granite quarries existed here owned by the Johnson Brothers. A railway system connected the different levels. Ernie produced a wonderful image from 1912 of the old winding house and wheel used to take the trucks up and down the incline plane (last used in 1868). Remains of an abandoned scheme to connect the quarries to the main railway can still be seen in the form of a bridge to cross the river – never finished. The old counting house and smithy has had various uses since the quarries closed, being a tearoom in 1910. Nowadays, it is known as Dewerstone Cottage, owned by Young Spirit, offering outdoor adventures from river scrambling to rock climbing, with a bunkhouse and campsite.

Down by the river is an old iron mine with two shafts still visible. Quite successful in the 1870’s , ore was carried across the river by horses up to Plymbridge Halt. The ore was also used for brickmaking, the old tunnel kiln with its intricate system of sliding doors still in situ. The Ferro Ceramic Company was wound up in 1873. In the National Trust car park are the remains of the china clay kilns and loadings bays – the clay being formed into blocks and thrown out onto trucks – still in use in the 1096’s. More of Ernie’s images showed how the blocks were stored to dry and an old cottage at the end of the row.

Still so much to be seen today of all these varied industries and a fascinating talk that was enriched by some beautiful old photos from their heydays.

The Civil War in the Tamar Valley 1642-51

A talk by Paul Reid

New Bridge, Gunnislake

Paul surprised us all by turning up in full period costume and with an array of 17th century weapons and artefacts on display. He started by explaining the differences in dress of the opposing forces of Parliamentarians and Royalists, completing a partial strip tease as he further explained how they both wore several layers of clothing which were interchangeable and adaptable to the cold conditions of the time.

Divine right, religion, revolution and republican ideals were all put down as reasons for the war. There was general distrust of the King who supported religious tolerance and favoured the local gentry, whilst Parliament wanted more power and working men’s rights. Devon was Parliamentarian but Cornwall was loyal to King Charles 1 and the Royalist cause. Thus, the River Tamar became an important battleground, Cornwall having some of the advantages of the monies from tin, secure harbours and ports for privateers..

In 1643 Parliamentarians led by the Earl of Stamford clashed with Sir Richard Grenville’s troops at the two river crossings of New Bridge (Gunnislake) and Horsebridge. The Royalists held their ground but suffered more losses through injuries inflicted by pikes, pistols, muskets and cannons. However, some over confidence from the men of Devon led to the Royalists taking advantage of hidden cannons to hit back forcing their opponents to retreat to Saltash.

Meanwhile, a Parliamentarian force led by James Chudleigh had landed at Falmouth and with fresh troops attempted to capture Launceston in a major battle at Polson Bridge. Once again though the Royalists held out forcing another retreat to Devon. There were further skirmishes though both sides retired to regroup and rebuild their forces as things quietened down.

By early 1644 with Royalists still in control of the Southwest, the Earl of Essex was leading a new army heading west and relieving the sieges of Lyme and Plymouth. At the same time, King Charles was also heading west to Exeter where his wife had given birth to Princess Henrietta and whose safety was at risk. Combining forces with Prince Maurice, the King passed through Tavistock and after further skirmishes at the Tamar crossings forced Essex’s army to retreat to Lostwithiel.

At the end of two weeks of fighting, the Parliamentarians were eventually defeated – Essex had escaped and the left in-charge Philip Skippon surrendered and accepted terms. Over six thousand prisoners were taken and marched to Southampton, many dying en route. The battle was the biggest defeat for the Parliamentarians and whilst securing the Southwest increased the popularity of the King for a while.

With peace again established there was a period of rebuilding. Bridges and walls were repaired and Royalist estates sequestered, However, there was local conflict on both sides over increased taxes, there were bad harvests and a fall in tin prices and general unrest, with major changes to come in 1645.

The Building of the Plymouth, Devonport & SW Junction Railway

A talk by Stephen Fryer

Stephen started by explaining the complicated set up of the various rival railways and the competition in providing lines into Plymouth – and beyond. With the broad gauge of the GWR already well established, they were against allowing the standard gauge to become the norm. However, with the Army and Navy expressing doubts about “ensuring the security of the district†the LSWR were finally able to put forward a proposal for a new line in standard gauge from Devonport to Lydford in 1882. Contracts were approved for £790K and work started in March 1887.

Over two thousand navvies were employed on the project and Stephen’s image of a typical gang embraced the times. All dressed in waistcoats but with a strict hierarchy: the boss with his top hat, the foreman sitting down at the front, they were a very hardworking bunch. Often living on site and “hot bunking,†with their wives cooking meals, they also had to buy their own tools and candles. Tavistock Hospital had just opened and many Navvies were treated there.

Via nostalgic images of then and now, Stephen took us along the 22-mile route from Devonport station with its footbridge – now the site of a Technical College, tunnels under Devonport Park and Ford, where the line passed under the main GWR line (only 4 feet above)! A sea of housing has now obliterated all trace of the old limestone and concrete viaduct which was dismantled in the 1980s with the limestone being used in the construction of the Plymouth Dome. At Ford Station, there is one of the first poured concrete bridges in the UK, now buried, along with the station, under spoil from building of the A38 Parkway. A small halt at Camel’s Head was used by dockyard workers, and at St Budeaux, the station even had its own covered walkway approach down to the platforms.

From here, the line still exists, picking up the GWR Tamar Valley tourist line to Bere Alston and Calstock. It passes over the stunning Tamerton Creek and Tavy viaducts, the columns all made from cast iron sections, sunk to the riverbed and then filled with concrete. Further on, another bridge disappeared after a disagreement over maintenance between local farmers. It continues past the picturesque station of Bere Ferrers and then Bere Alston, once very busy from the valley horticulture and flower trade and from where the tourist line branches to Calstock.

From the latter, remains of the line to Tavistock are dominated by the Shillamill tunnel and viaduct, although many of the original features of the route are now obscured by dense vegetation. Another viaduct towers over the town into the old station though the former footbridge is now on the Plym Valley line at March Mills. Heading out into the countryside, the route passed through Wringworthy, Mary Tavy and Brentor – the old station here now carefully looked after in private hands. At Lydford, the GWR and LSR lines are merely yards apart. Old wartime sidings are lost in the undergrowth. The line was built with 3 tunnels, 7 viaducts, and 76 bridges, but by 1968 was closed, along with the ongoing route to Okehampton.

A talk of fond memories enhanced by Stephen’s thorough knowledge, plus input from the incomparable Bernard Mills and their stunning images of the infrastructure and the old engines. Perhaps current discussions about restoring the link from Tavistock to Bere Alston may bring some of these back – without the steam of course.

The Beardown Inscriptions

A talk by Simon Dell

The Bardic stones, courtesy of Simon Dell

Edward Atkins Bray was born at the Abbey House (now the Bedford Hotel) in Tavistock in 1778. His father, a solicitor and steward of the Bedford Estate, had bought Beardown farm and it was here that Edward spent his summers beside the Cowsic river, developing an interest in poetry. Simon’s entertaining talk went on to explain how one man’s dream came to fruition.

On the wishes of his father Edward started training as a lawyer in London, subsequently qualifying and working on the circuit. However, realising he preferred a quieter vocation he turned to the Church. When the Vicar of Tavistock died, he took over the role in 1812 moving into the new vicarage in 1819. Four years later, he married Eliza Stothard whose husband had been killed in a fall at Bere Ferrers church. She went on to become Tavistock’s most prolific author.

Bray was clearly a great lover of nature, the connections with the spiritual worlds and the role that poetry played in bringing these together. One of his carvings illustrate this -â€Sweet poesy, fair fancy’s child: thy smiles imparadise the wildâ€â€¦He became obsessed by the Greek and Roman poets, the Druids, Merlin the magician, the Isle of Mona (aka Anglesey, an old haunt of Merlin’s). Also, a visit to the British Museum to see the Rosetta Stone, perhaps inspired him to create his own vision.

Thus, over a period of about 5 years, in the little wooded valley of the Cowsic, Edward had inscriptions carved on the rocks about his favourite poets. Some of these are in couplets though lack of space and suitable rocks meant most of these were just dedications. Although many were hidden under dense undergrowth for many years, Simon and his team have now uncovered 28 of these. Two are inscribed in Bardic runes – the Celtic “Sprig†alphabet – and have been translated. His Isle of Mona sits in the middle of the river and nearby is the grotto of Merlin’s cave. On one stone the writing is upside down, probably due to the rock having been moved in a flood.

Through Eliza’s famous notes and letters and her correspondence with the Lake poet Robert Southey, many of Edward’s more detailed intended inscriptions have been discovered. For instance, on one of the stones in Merlin’s Cave – “these mystic letters would you know – take Merlin’s wand that lies below.†There would be a white wand with Celtic letters alongside one in the Roman alphabet. Held together would have enabled translation. (Incidentally, Simon produced his own version!).

Edward died in 1857 after 45 years as the Vicar of Tavistock and is buried beneath the cloister arch at St. Eustachius church. In the rock inscriptions he has fulfilled his dreams and left a legacy of his love of Dartmoor and the natural and spiritual world.

Simon will be leading our members on a visit to these special places in August.