A Tale of 3 Schools; Preserving Tavistock’s Eduacational Heritage – a talk by Will Hay

Will Hay from Tavistock Area Support Services (TASS) provided our last talk of the year with his presentation from the National Lottery Heritage funded “Life Stories Project”. Delving into the experiences of ex-students during the 1920s to 1960s, from three schools in Tavistock, namely Dolvin Road Secondary Modern (DRSM), the Grammar School (TGS) and the later Comprehensive (TC); the project explored the students’ school memories and the impact of their schooling on their lives that followed, with volunteers undertaking interviews in person and by phone.

Several of the students interviewed had experienced the transition from TGS and DRSM to TC and these were mixed. Some were overwhelmed by the increased size of the TC, opening in 1959 with over a thousand students, likening it to a “factory”, with the absence of discipline and an orchestra! One was delighted by being reunited with old primary school friends who had failed their 11-plus. Memories of teachers varied a lot from those that were very good and influential to those who “didn’t have a clue”. Their ability to maintain order came into question and the recollections of corporal punishment at the time are interesting given how that would be perceived today. Perhaps surprisingly, there was little remembering of bullying amongst pupils though prefects could often be vindictive at TGS but not at TC.

One student said “there was a lot of free rein, which I think took the pupils into a good position to move on either to study or further their careers. It gave them self-confidence. I think that the school probably had an excellent balance”.

Several of the interviewees said they enjoyed school and were happy there, though often “drifting through” without much interest in learning. As extra activities and clubs were brought in at TC, there was more perceived enjoyment of school time, including in choirs, debating societies, astronomy and judo clubs and general sport.

As many of the students interviewed had since moved away from the area, their affinities to Tavistock were examined. Some said they couldn’t wait to get away going off as far as they could for jobs and university. However a lot still had family ties and seemed to say that the area “is in my blood”, often returning for holidays, some back to stay and pursuing careers and life locally. They were drawn by the beauty and outdoor life of Dartmoor and the Tamar Valley.

Looking back on their days over the 3 schools some said they wished they had tried harder and not “messed about”. One thought that the grammar school was a bit dull and more going on when it came to the “comp.” – better buildings and sports facilities, younger and less stuffy teachers. One “embraced the changes” to the larger schooling and social environment.

Overall, the schools of Tavistock seem to have left an indelible memory of mostly enjoyable times with the town and the area remaining with the students through their lives. A fascinating project which was well illustrated by Will invoking memories amongst all of us of our educational heritage.

Manuscript Maps of Devon – a talk by Dr. Todd Gray

Before 2002 maps had gone out of fashion but then the book called “Devon Maps and Map-Makers Manuscript Maps before 1840” by authors Margery Rowe and Mary Ravenhill was published in two volumes containing over 1300 entries. Digital images of these maps which were held privately and out of county and acquired during the authors’ research are now in the Devon Heritage Centre in Exeter. Other institutions like the Somerset Record Office, British Library, and The National Archives also hold some.

Dr. Gray explained how in his own research he discovered that many of these maps had lain hidden away in the dusty attics of private collections for hundreds of years but has since uncovered many fine examples, some going back to the 15th century, which he then proceeded to display. One of the first from 1665 was of the Boringdon Estate in Plymouth, clearly showing the maze, canal and other garden features.

An early 17th century map of Ashburton he described as pretty but useless! A Victorian copy of a 1590 Crediton map shows details from before the great fire of 1743 highlighting the old cob and thatch buildings. Kingsbridge featured in a copy of a 1540 original and one of Haccombe House (owned by Carew) was a map lost for several hundred years before rediscovery.

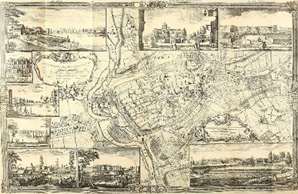

Many of the old maps show fine details : a 1566 Paignton map with benches placed outside homes; a 1619 Dartmouth – the mill pond; slate roofs in Cullompton and long gardens and allotments in Thorverton. Found in the Bodleian archives was a Richard Newcourt map from 1640-70 of old Barnstaple (Barum) – depicting the town gates, the stone Long Bridge, and other important structures of the period including quays and the castle. The author prided himself on accuracy of scale by pacing out the distances on the ground. An early 17th century map of Bideford is 10 feet long.

Exeter features in many of the early maps. John Hooker’s 1497 one of Exeter is very colourful, clearly showing all the Norman churches, the city gates, medieval bridge and cloth making buildings. A 1605 leather map found in Kent had been owned by an Australian opera singer – sadly since sold and whereabouts unknown.

RW Townsend was another local collector, his 9 maps of Exeter tracing the development of the city from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. One in particular has images of tar barrels in the street, an “air purifying” feature common in the cholera outbreak of 1832. John Roque was another, his 1744 map shows individual buildings, listing them by owner with a key to their identities. A further unusual departure from an actual map was a scale model of the Exeter South Gate and the debtors’ prison, purportedly produced from the boyhood memories of the creator.

Todd has himself built up a collection of these ancient maps, often having to keep an ear open for items coming up in auctions. He believes there are still a great many lost in private collections awaiting re discovery though some may now be gone for ever. Clearly they are of significant historical importance with their unique pictorial style.

A landscape History of the Lower Tavy, Maristow and Blaxton – a Tallk by Sharon Gedye

Sharon gave us an excellent talk with good overheads and illustrations by means of 9 interesting points.

The Crossings – there were 2 main crossings Lopwell Ford and Chuck’s Ford used for centuries as the lowest crossing points of the Tavy to the Bere peninsula. Lopwell was just above the present dam which was constructed in 1952. Chuck’s Ford was unsuitable for cars. Tragedy struck in 1905 when Robert Henry Lawrence drowned attempting to cross. Ferries also operated including Blaxton ferry, which existed in 1263, indicating the area’s long-standing importance in local transportation.

The Chapel of St Martin of Blakestana – dating back to the 12th century, the chapel was granted to Plympton Priory. Charters from the mid-1100s and 1225 confirm its existence and connection to a possible sacred spring. The medieval chapel was later demolished and fragments incorporated into a 19th century ‘folly’ near Maristow House.

Maristow House – Originally owned by Plympton Priory, it became a grand estate post-Dissolution. The Champernowne family sold it and it passed through several hands, including those enriched by Caribbean slavery, James Modyford Heyward and later Sir Manasseh Lopes significantly renovated it. The house experienced several fires, wartime requisition, and a school, survived a threat of demolition and eventually redeveloped into luxury apartments.

Blaxton Woods – These woods contain mysterious architectural features like a ‘turret’ which is likely ornamental and linked to a royal visit by George III in 1789. New ‘roads’ and possibly these structures were created for the ‘visit’, turning the woods into a designed romantic landscape.

Blaxton Mill and Quay – Established in 1822 for flour milling, the tidal mill was blown down and then damaged by fire. It featured a large waterwheel and the current ruins represent the area’s industrial past; the last know miller was listed in the 1861 census.

Fishing Rights (AD 1369) – A 14th century charter confirms the fishing rights of Plympton Priory along the river, outlining detailed provisions for methods (like ‘Hakynge’) and the rights of inhabitants of Blaxton to fish for sustenance, reflecting the river’s historical importance for food and the economy.

The Roborough Hoard – the Roman coin hoard includes rare sestertii from the early Imperial period (AD 37-43) providing evidence of Roman military activity west of Exeter at the start of the invasion of Britain.

Silver Mining – From 1292 to 1349, the Bere Peninsula had royal silver mines but their administrative centre and refinery was Maristow. The industry decimated 300 acres of woodland by 1300 AD.

The Wolf Pit – A 13th century charter describes the land gifted to the priory and the chapel and included in that is the mention of a wolf pit. By this time wolves were getting scarce but still problematic as they were predators of sheep so trapping pits were necessary.

Today, Lopwell and Blaxton are seen as tranquil places but were once very busy and strategically important.

A Heritage visit to Ford Park Cemetery, Plymouth

To the background noise of the Argyle Green Army and dark clouds overhead, Alan and his assistants Margery, Vivien and Lindsay took us on an interesting tour of this historic site of around 250k burials.

Alan started with a brief history of the site, going from green fields in 1840 to become a private and the main graveyard of Plymouth because of severe overcrowding and closure of the other city cemeteries due to public health concerns. After 50 years of virtual monopoly, competition from new crematoria led to a gradual decline and the company and the site closed in 1999. However, just a couple of years later, a new Trust was formed and much restoration and improvements have since been made.

Our guides then took us around to visit the resting places of notable “residents,” starting with the ornate marble memorial of Joseph James Spooner (died aged 44) and family. Along with his wife Ann he founded the famous local firm of drapers, their store destroyed in WW2, then becoming Yeo and Debenhams, closing finally in 2021.

Another famous local company is remembered with the unmarked grave of Ann Farley, who started life as a baker, then created Farley’s Rusks, eventually sold to the Trehairs, now the site of a Morrisons store. A Sgt. Henry’s life is also celebrated with an annual remembrance by family and friends – he survived 12 bayonet wounds in the Crimean War receiving a VC for his efforts. Continuing on we passed the memorials of a Thos. Bridgeman a lion tamer and the Whiteleggs of fairground fame who lived in nearby Stoke and started off in 1916 with the invention of a juvenile roundabout ride..

Around 500 war graves in grey Portland stone stand solemnly opposite the 15 plain white crosses of the A8 type submarine squadron. George Hinkley is close by, another recipient of the VC as a survivor of the Opium Wars – a somewhat dubious character who nevertheless also commands an annual remembrance ceremony. We passed several other graves with intriguing stories told by our guides, ending up with a splendid memorial to a John Coath, “murdered by savages” in Espiritu Santo (modern Vanuatu). It seems he was a slave trader and the locals objected rather strongly!

Much restoration has been done on the 2 chapels which were originally built in the 1850’s. The Victorian Chapel (pictured above) now has a huge wall plaque, engraved with the names of over 1,200 civilians who died in the city in WW2. It is itself a tribute to the work of Dr. Henry Will who pioneered the early work of the new Trust.. The original Non- Conformist chapel was destroyed in WW2 but the new version now houses the heritage centre where research can be conducted with the aid of the huge site database.

We ended our visit here with tea and cakes in the café. This is a fascinating site with much more of interest than can be seen on our short visit or detailed here, but with the help and knowledge of Alan and his assistants, many might want to come again.

A visit to the Prisoner of War cemeteries at Dartmoor Prison – with Paul Finegan

Paul, curator of the Prison Museum, led us on a highly informative and entertaining visit to the American and French Prisoner of War cemeteries in Princetown, followed up by a walk to the local church.

As we made our way towards the imposing entrance gate, Paul explained about the origins of the prison and how Thomas Tyrwhitt, private secretary to the Prince Regent and the owner of the vast Tor Royal estate conceived the idea of a prison. At the time there were two other prisons in Peterborough and Bristol but, when these became full, the French prisoners from the Napoleonic wars were held in hulks in the Hamoaze in very bad conditions of overcrowding and disease. Already realising that his dreams of making money from agriculture on his land were in disarray, Tyrwhitt had a brainwave. Furthermore with the availability of building stone and fresh water…….the prison opened in 1809 accommodating over 6,000 inmates. This was doubled later by US prisoners from “the forgotten war of 1812 .”

Between 1809-14 it held over 12,500 prisoners with 1,500 deaths, bodies interred in the local fields. The prison closed in 1817 after the end of the wars and reopened in 1850 as a convict prison.

Paul led us down alongside the huge exterior wall explaining how the prison once operated its own farm and quarry, many of the buildings including stables for the horse patrols, still evident today. At this point he regaled us with amusing stories of attempted escapes and a case of where the bureaucracy of listed buildings status ruled over necessary deterrents. As the farm started to be cultivated, bones from the burials began to appear so the remains were exhumed and reburied in 1866 in the newly created cemeteries.

They stand in landscaped grounds, having been significantly revamped in 2002, both poignant reminders of the horrors of war. The French memorial obelisk is modest having been made by prisoners and in 2009 on the bicentenary of the first French prisoners of war transferring from the hulks to the Prison, a ceremony was held here attended by descendants of the prisoners of war and French dignitaries.

The American side is rather grander with an obelisk and its two marble memorial walls containing names of the 271 POWs who died, the youngest of which was only 12 years old. Names such as Placid Lovely, Dumpy Kitre and Shadrack Snell add to the sense of sacrifice. The National Society “Daughters of the War of 1812” make occasional visits.

With the wind still battering us, we concluded our visit with a walk to the church of St Michael and All Angels which was built between 1812-15 with assistance from the American and French prisoners of war. Now redundant and maintained by the Churches Conservation Trust, it has may interesting interior features and outside graves and monuments. One of these commemorates the three men who perished in a snowstorm near Soldiers Pond..A visit of stunning historical facts made hugely interesting and entertaining by Paul’s knowledge and humour.

Plymouth Synagogue visit – with Jerry Sibley

We congregated in Catherine Street outside the synagogue (or meeting house) and were given a brief history of the area by Jerry Sibley, the synagogue’s custodian. The street was named after a visit by Catherine of Aragon and buildings have also included a workhouse which then became the police station and a public dispensary. The dispensary and the synagogue were the only buildings to survive the WW2 bombing of Plymouth but the area has been much built up since encircling the synagogue. At one time the street was twice the length it is now with the caretaker’s house facing the street and originally attached to the synagogue, being now above the school room. There was also a Hebrew school, the remains of which are under the Guildhall. A new school was built opposite the entrance in the 1840s.

Jerry explained that he is ˜the slave” who does all the jobs that Jewish people are not allowed to do on the Sabbath which starts at sunset on Friday. An ex-soldier, he discovered that the synagogue was likely to close due to lack of funds and had the idea of opening it to the public for free guided tours but receiving donations. He has extensively researched all areas of the Jewish faith and now teaches at schools, 74 last year

The synagogue itself was built in 1762. The hallway is an extension and holds the rolls of honour from the world wars. Inside, the gallery was extended in 1864 and paid for by Levi Solomon who later went to the USA, changed his name to Simpson and his son married Wallis of Edward V111 fame. In Judaism ladies are the more important and they can sit in the gallery with the children (boys up to 13 only): the men oversee the service and must attend.

The congregation kept on growing and at one time had at least 3,500 men with many of its members (as tailors) supporting the local naval economy. As this diminished and houses were not built nearby after the destruction of WW2, many moved away as they were not permitted to drive but only walk a short distance to the synagogue. As a result some moved to London and Manchester and then to the State of Israel which was created in 1948. In 1968 the membership was so low that there was no longer a Rabbi and is now only 39 in the whole Southwest.

The beautifully ornate Ark, built by the Dutch in 1761, is on the eastern wall, made of wooden plaster and having survived the war. It holds the scrolls which are sung during the service. In the centre of the synagogue is the Bimah, the platform from where the services are conducted and built by naval carpenters to look like a ship, again quite ornate with 8 candle sticks topped by acorns.

To finish our visit, Jerry invited us to take part in some role-playing. First, he explained the various elements of a service, and then described each of the main participants, from the Rabbi (teacher) to the ‘slave.’ He dressed volunteers from the group with the appropriate robes and told us how each person assisted with the service.

The Synagogue is a fascinating place to visit with Jerry, a truly knowledgeable and entertaining guide.

“When the Judge shot the Doctor: Devon’s Last Duel – a talk by Prof. David Pugsley

David regaled us with this fascinating tale of an extremely popular doctor who was fatally wounded by a fellow Irishman in a duel on Haldon racecourse.

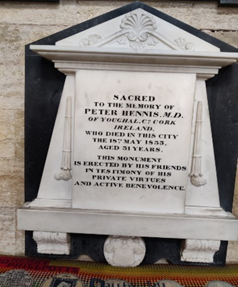

Dr. Peter Hennis was from a military background; his father having been Commandant at Youghal barracks. He was educated in Edinburgh and came to Exeter with no job. But he achieved great popularity in 1832 during the cholera outbreak, where he worked for the Exeter Dispensary treating the poor and children considered unfit to be admitted to the Devon and Exeter Hospital. He devoted a great deal of time to their care also organising fund raising functions to help the sick.

John Jeffcott came from Munster, an area with a strong tradition of public duels. Educated in Dublin, he had a strong liking for wealthy women to marry. After entering law, he became the chief justice in Sierra Leone aged 34. He was active in opposition to the slave trade, but after living in a poor climate with disease and poverty, came back to England in 1832 seeking a rich wife.

At about this time, Dr Hennis was courting a Miss Clack, the daughter of a local parson. Whilst riding with the parson on a hunting trip and enquiring about the daughter, Jeffcott was supposedly told that Hennis had warned the daughter about him, calling him “an amoral coxcomb”. These details were recorded in what was claimed to be Jeffcott’s journal. However, this has since seemed doubtful as the dates do not tie in with him being already in England – more likely to have been concocted by a Robert Holland who also had eyes for Miss Clack.

However, Jeffcott treated the comments as a dreadful slur, calling Hennis a “damned calumniating scoundre.” On top of this, Hennis was about to marry Miss Clack the following day when Jeffcott was due to return to Sierra Leone. In true Irish tradition Jeffcott challenged Hennis to a duel. This took place on Haldon racecourse on the 10th May 1833 with only 5 persons present as witnesses. Although the rules allowed the insulted person to fire first, it was thought that Jeffcott had fired early, possibly by accident. Nonetheless, Hennis was shot in the stomach and was seen by a “passing doctor” to be writhing on the ground in severe distress! He died 8 days later.

Jeffcott was indicted for murder but left for Senegal. The following year he was knighted for his services abroad. But after negotiating with prosecutors, he returned in 1834 and stood trial. He was subsequently acquitted as under the law; there was no evidence! Duels were illegal and thus none of the witnesses came forward.

He went on to become Chief Justice in South Australia in 1836 and married a rich farmer’s daughter. However, on an expedition to the Murray River, his boat capsized and he was drowned.

The city of Exeter was said to be outraged by the death of the doctor with 20,000 people lining the streets as his coffin was carried from his funeral at the cathedral to its place of rest at St. Sidwell Church. A blue plaque commemorates him today in Sidwell Street..

“The Tavistock Workhouses” – a talk by Nicki Gurr

On a wet and windy evening in April we all attended this talk by Nicky. She had used various sources for information including censuses, books and online information.

The first workhouse was on Lower Brook Street, established in 1747, which housed about 50 inmates with the old leper hospital for any overflow. Poor repairs and financial management meant that in 1810 a request was submitted for a new one.

In 1817, the second workhouse was placed to the west of the town on Ford Street and built on the grounds of the old leper hospital. It had the capacity for 100 people but usually had no more than 75. This workhouse was used for about 20 years before Bannawell was opened. According to reports in the 1830s conditions here were harsh and inmates lived in segregated areas with barred windows, sleeping and eating in the same room.

The third workhouse, built following the Poor Law of 1834, was known as the Tavistock Union Workhouse and replaced local parish workhouses. Tavistock was an average sized parish with a population of 20,630. This workhouse, built in 1837 at a cost of £7,000, was designed for 210 people and overseen by 35 guardians and inspected by the Poor Law Board. The master’s and matron’s quarters were in the centre and sections for the different classes of inmates either side: women one side and men the other and so, if admitted together, families were separated. Young children stayed with the women. There were also exercise blocks and an infirmary to the north of the site.

There were 4 main groups of inmates: itinerant labourers, expectant mothers, the elderly and orphaned or abandoned children. Over time the workhouses turned out to be a combination of orphanages and old people’s homes. The number of young widows reflected the conditions of the local mines. Vagrants had to seek permission with a ticket from the local police as evidence for entry.

The breaking up of stones was the primary job for long term male inmates if they were strong enough. The women mainly plucked oakum or made clothes for the other inmates, worked in the vegetable garden, the infirmary or the bakery.

Children under 7 were housed on the women’s side but after that were moved to the men’s. For education there were separate classrooms for boys and girls with workhouse schools complying with general educational rules in that they were educated until the required age.

Guardians, often prominent people, were elected from each parish and came from a range of professions, largely from the farming community but also innkeepers, post masters, accountants and vicars. The Board would meet fortnightly to discuss issues. Lady guardians started to be elected in the 1890s.

Teachers were responsible for more than just teaching whereby their day began at 5.45 getting the children ready for the day and ending with putting them to bed at 7pm.

We thank Nicky Gurr for a most interesting talk.

The History of Dartmoor in 10 Objects – a talk by Andy Crabb

Andy’s talk took us from the bone caves at Buckfastleigh 125,000 years ago to the present resurgence in the growth of the cider industry, bringing along as well some of the artefacts found among Dartmoor’s 3,500 scheduled monuments.

The Joint Mintnor cave had revealed many bones of that period, including those of the 11 ton straight tusked elephant, a vegetarian browsing in the warmth of the abundant forests. By the Mesolithic period, just 14,000 years ago, in the stable climate of the post Ice Age, hunter gatherers were on the scene. Evidence exists from Whiddon Down of a very advanced society with cutting tools and organic clothing

A Neolithic hand axe found at Postbridge was passed around, more evidence of further sophistication as farming began to develop. The peat bogs were expanding and monuments appeared – stone circles, tor enclosures, dolmens like Spinsters Rock – all perhaps meeting places or symbols of power – maybe the first such built in the UK.

One of the most astonishing recent archaeological finds dating to the Bronze Age was at Whitehorse Hill. Excavation of a burial cist had revealed bones and items from an elaborate burial – beads, wooden studs wrapped in a brown bear pelt. We await now too the results of the latest discovery of a log coffin on Cut Hill. Hoofprints in the soil have given us further proof from the middle Bronze Age of cattle, ponies, sheep and badger, as hill farming and enclosures (reaves) began to take over.

The period that followed saw the abandonment of the high moor as humans settled on the fringes. Lydford was an example of a 10th century fortified settlement, creating its mint of 1 million silver pennies. A lot of these have since been found in Scandinavia, remnants of payments for Danegeld. A strategic location, it had its own castle and jail. Excavations at Widecombe have revealed remains of the ancient manor of North Hall with its ditch and moat. Pottery found here is believed to have come from Eastern Europe and China.

The Moor is littered with the remains of the tin industry, from the early stream working of the 12th century through to the later open cast.workings. Hardly a river course has been spared the efforts of these workers, their tin mills, blowing houses, leats, wheel pits, mortar and mould stones abound, uniquely just here and on Bodmin Moor. Later, the stone workers take over in their quarries with unfinished items like granite rollers and troughs still found today. More recently we see evidence of the “improvers” – railways, canals, turnpikes and china clay.

Andy finished his talk with the mention of Dartmoor cider and its use of horsepower, Old apple crushers and troughs can still be seen, evidence from a lively industry supplied by produce from local orchards.

Enhanced by items he brought along such as an arrowhead, a stone cutters jumper tool, a silver penny and a Bronze Age axe, Andy produced a stunning talk of the varied archaeology of the Moor.

Excursions in the Tamar Valley – a talk by Helen Wilson

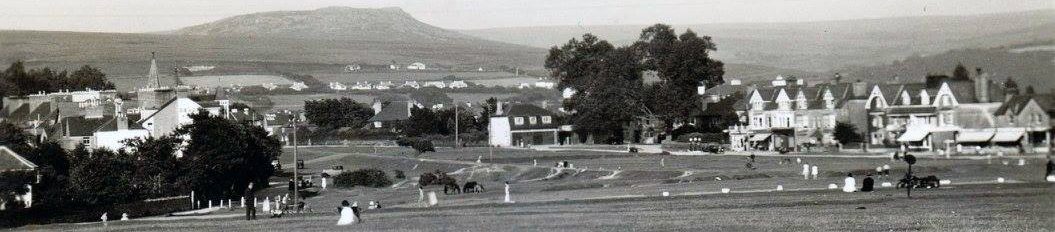

The Ashburton Hotel 1890 (Francis Frith collection)

Through her large collection of old postcards, created by various famous photographers including Valentine, Frith and Harris (mostly from around the end of the 19th / early 20th centuries), Helen led us on a nostalgic journey around the river valley. On her pictorial map she highlighted the points on the river where people made their way by various means including on foot and by ferry and paddle steamer.

Foot perambulations often started on the Hoe and an early card image by Valentine depicting Smeaton’s Tower and people thronging around the bandstand captures the moment perfectly. More cards show the Cremyll Ferry and points of interest at Mt. Edgcumbe, from where a steamer would have taken the walkers on to Antony Passage and Forder, stopping for refreshments at Apple Tree Cottage Tea Gardens. More tea stops in Saltash and back across the river by ferry. A Western Morning News advert as early as 1860 announces trips on the steamer “Fairey” to the tea and fruit gardens of the West, all for the price of one shilling!

Steamer trips left from Phoenix Wharf, with images from the 1880’s showing Promenade and West Hoe piers, several steamers queuing up and the “Eleanor” setting off. The battleship HMS Hood is seen in a scene at North Corner. At Weir Quay, fishing nets are seen drying on the shore and an ales and tea stop came next on the agenda at the Tamar Hotel in Holes Hole. Past Pentillie Quay and on through “the Windings” to the Ashburton Hotel at Danescombe with its market gardens and then the rather more industrialised area of the Calstock shipyards and more refreshments at the Ferry/ Passage Inn across the river. An image of the old ferry here is pertinent given the current interest of resurrecting the service, albeit an electric one.

Steamers were able to continue upriver past Buttspill Woods to the ancient port of Morwellham – an image is seen of the area still working in 1870 with inclined planes and tramways clearly visible. A later one by Frith in 1906 post closure is a much quieter scene. A card from 1911 is interesting, still showing lime kilns and the workers houses at New Quay. Journeys ended at Weir Head. Helen showed several images here, one of the old Dukes Drive which closely followed the riverbank and others by Madge of Morwell Rocks and a steamer passing underneath. The terminus at Gunnislake Weir and the line of the Manure Navigation Canal can also be seen in a card from 1931.

It is clear from Helen’s talk and stunning postcard images how popular it became for people at that time to undertake such journeys, linking their walks around the Tamar valley with ferries and steamers, with many opportunities for stopping for refreshments along the way. Although still popular and busy, the area is vastly different today.

Sabine Baring Gould of Lewtrenchard – a talk by Vanni Cook

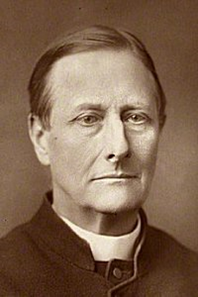

Sabine B-G was born in Exeter in 1834 and died in 1924. He was many things including : an Anglican priest, Vicar, Hagiographer, Theologian, Hymn Writer, Antiquarian, Historian, Archaeologist, Popular Novelist, Poet, Gatherer/Collector of Folklore and Folk Music, Father, Husband, Friend, Family History Researcher, Conservationist, Environmentalist, Geologist and Recycler.

Vanni’s talk explored his family background and personality wondering why, despite all his interests, he seems to have been somewhat overlooked compared to his contemporaries. He had graduated at Cambridge University (BA Arts), spent time at Hurst Pierrepoint and Clare Colleges, plus a spell in Iceland studying their sagas, before being ordained as a Mission Priest in 1865. He served as a Curate in Dalton, Yorkshire, was married a year later to Grace and their first child, one of fifteen, was born in 1869.

He inherited the family estate of Lewtrenchard upon the death of his father in 1872 and began the restoration of the church 5 years later. After becoming the Squarson in 1881, he continued further works to the church and remodelling of the manor house well into his later years.

His personality was shaped, said Vanni, by bronchitis, a patchy education (though he was fluent in 5 languages), a controlling but inquisitive father, a hatred of sport, loyalty to friends and family and a great sense of humour, with a nickname of “Snout”. This was evident in character roles he played at college and letters he wrote during his many travels. He brought back a souvenir from Iceland, a pony called Bottlebrush! He also loved word play of any kind and this is shown through his love of witty anecdotes and local dialect.

As a writer he had over 1,200 publications and was credited by J.M. Barrie as being one of the top ten novelists of his day, also attracting reviews from George Bernard Shaw. Red Spider (1887) regarded by the author as his finest work, draws on his interest in rural life, folklore, and mythology.history. As a play it was performed over 100 times around the country.

In 1864 he founded the “Brig Mission” at Horbury Bridge in Wakefield, a church school, still going today. In the following year, after buying a plot of land, he founded a new mission church and school – this building still stands and is now part of the present school site. It was here too that he composed the hymn “Onward Christian Soldiers,” as a song for children marching up the hill to the church.

He founded other Christian schools and furthered education especially for women. The love of his family and loyalty to friends and employees was also highly regarded. His kindness is evidenced in the scores of letters to and from school mistresses, employees and associates.

Overall, a fascinating man.